I am in Washington DC at the Brookings Institution participating in a conference based on the papers that will appear in the next issue of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, and specifically to discuss a paper called “Income Inequality, Social Mobility, and the Decision to Drop Out of High School.”

The authors, Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine, say in the abstract of their paper:

we posit that greater levels of income inequality could lead low-income youth to perceive a lower return to investment in their own human capital. Such an effect would offset any potential “aspirational” effect coming from higher educational wage premiums. The data are consistent with this prediction: low-income youth are more likely to drop out of school if they live in a place with a greater gap between the bottom and middle of the income distribution. This finding is robust to a number of specification checks and tests for confounding factors. This analysis offers an explanation for how income inequality might lead to a perpetuation of economic disadvantage and has implications for the types of interventions and programs that would effectively promote upward mobility among low-SES youth.

You can learn more and download the paper from the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity web site for the 2016 Spring conference.

The slides for my discussion of the paper are here.

My comments revolve around three questions raised by this nicely crafted paper:

- Inequality of what?

- the authors focus our attention on the degree of inequality in the lower half of the income distribution

- but they also use a measure of inequality based upon all sources of income, including benefits from government transfers

- so policy makers might wonder about the scope and design for government transfers to lower inequality in the lower half, and in particular of expanding the EITC to include men

- Social Mobility for whom?

- state-level inequality raises the chances that boys from low status backgrounds will drop out of high school, there is no statistically significant influence for girls

- but these patterns also depend upon the abilities that these boys have when they start high school

- I show that these abilities are actually correlated with the abilities children have when they were kindergarten age, so we might also wonder about whether policy should be directed to individuals and high schools, or to families and young children

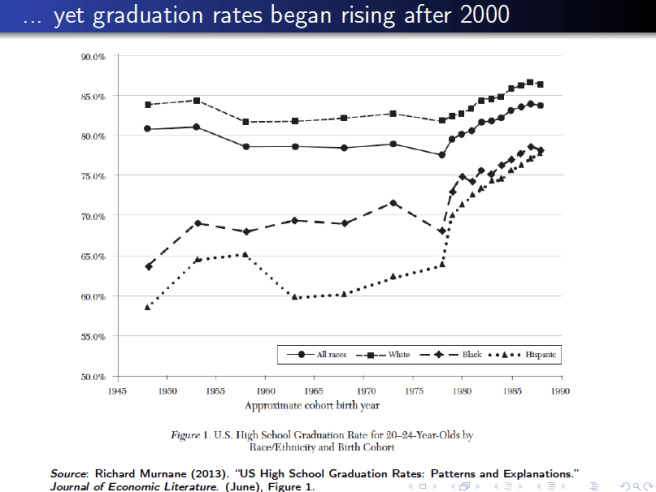

- Whither Dropping Out?

- the trend in dropping out of high school has actually been on the decline since about 2000, yet inequality has not changed that much during this period

- but this paper helps us to think more constructively about trends, it may be that the degree of disenchantment about future prospects have changed