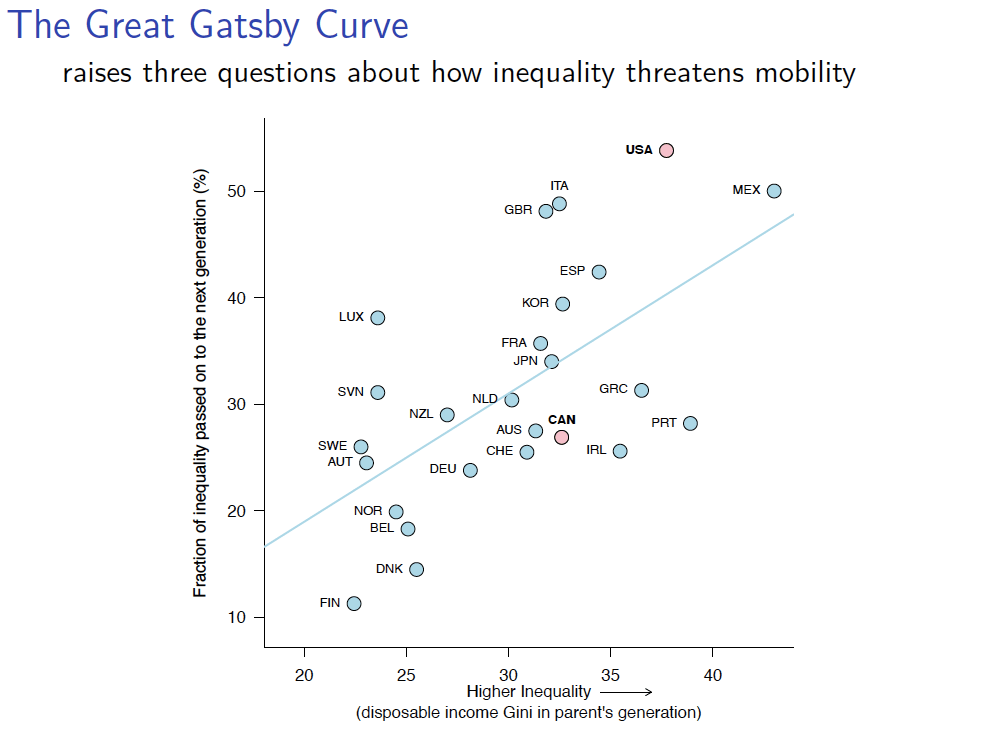

Inequality erodes opportunity, and limited opportunity exacerbates inequality.

This vicious inter-generational cycle has brought inclusive growth into question, contributed to the rise of populist sentiment, and strained the social contract in many rich countries. The way forward for researchers and policy makers requires not only a clear understanding of the facts about what kind of inequality matters and how it matters, but also an ethical grounding that speaks to the outcomes and opportunities that are important to citizens not only in the here and now, but also in the next generation.

This is the major message of a presentation I will be giving to the faculty and students of the PhD program in Economics at The Graduate Center of The City University of New York, where I am lucky to work and teach. My presentation—which also has the great benefit of being discussed by my soon-to-graduate PhD student, Aman Desai—makes this case by addressing three related questions

- What do we care about?

- We care about self-realization that contributes to an expanding and inclusive community that in turn enhances the capacities of its members to become all that they can be. And this involves caring about a sense of progress, a sense of movement toward security and inclusion, and a sense of fairness.

- What do we measure?

- Empirical researchers studying intergenerational mobility need to align what they measure with what we care about, which asks for an eclectic use of statistics and a sometimes subtle appreciation of how they relate to what we care about.

- What should we do?

- Certainly public policy should be evidence-based, but it needs increasingly to be ethically-grounded, with researchers bringing their numbers to public policy by explicitly making their own values clear. In my view, three values should guide public policy toward what we care about: all humans are equal, and should be treated with dignity; labour has preference over capital; and wealth is created to be shared.

But what gives this presentation an extra spice, at least for me, is that April 10th, 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, The Great Gatsby. So it is fitting for me to begin the presentation with a bit of biography on how the Great Gatsby Curve got its name!

Feel free to download the presentation slides, and certainly if you are at the Graduate Center, to attend the presentation!