The COVID19 pandemic will threaten social mobility. I examine three ways in which this is likely to happen in my presentation to the ZEW Seminar on COVID19 and inequality held on June 19th, 2020. This post summarizes the major messages.

Drawing on past research I see three aspects of inequality in the lower part of the income distribution that will be exacerbated and threaten the upward mobility of children raised in challenging circumstances.

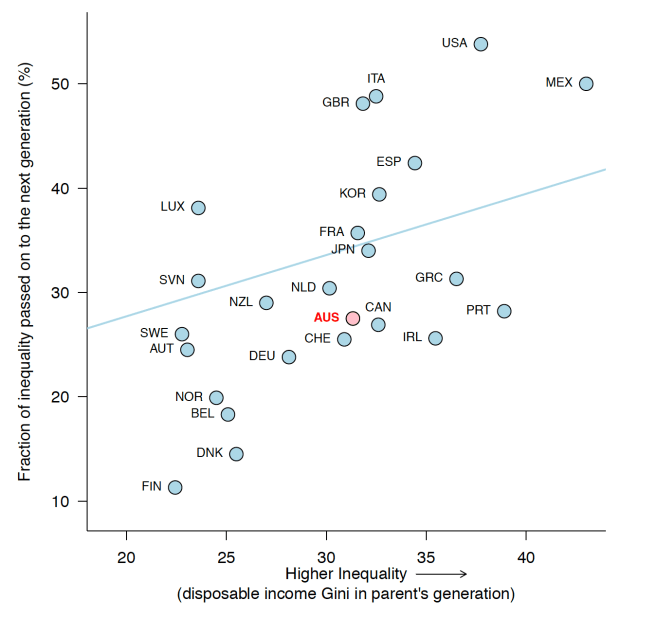

But I begin by stressing that the United States has lower social mobility than many other rich countries in part because of a more vicious intergenerational cycle of low income, and this in turn has something important to do with race and a legacy of disadvantage among African-Americans.

The obvious challenge for public policy directed to enhancing equality of opportunity is to address the barriers that divide many from the mainstream, and to promote social inclusion of all.

1. Family is central to social mobility

But more specifically, COVID19 is likely to have exacerbated the challenges of parenting, family stress has likely gone up among some families, and in the extreme abusive relationships are more threatening and harder to leave. Separation and divorce may rise. From the perspective of the adult prospects of children, this will lead to delayed partnership formation, and more unstable relationships, even if it does not impact directly on their earning prospects.

2. Progressive public investment matters and should be supported

Social mobility is promoted by progressive public investment, particularly in health care and schooling. Many have already pointed out that the pandemic has exacerbated differences in schooling outcomes in the short term, as children in lower socio-economic families have gained much less from online learning than their counterparts. This is equivalent to the well documented loss in learning that occurs during summer months as well-to-do families enrich the child’s experiences in ways not available to others.

But in the longer run it will be very important to not cut back, indeed to increase, investment in high quality public schooling. An era of austerity in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession led to cuts in public investments that should be avoided this time around.

3. Job loss and income falls echo into the next generation

Finally, if temporary layoffs morph into permanent job loss, and if public income support is inadequate this will imply a long-lasting decline in family income that will have long run consequences for children. The adult earnings of children raised in families where the main breadwinner permanently lost a high seniority job in mid career suffered. The parental income loss echoed into the child’s adulthood, the children experiencing lower income and greater reliance on public income support as adults.

For more detail, download my presentation and use the links to useful resources to learn more: “Inequality from the Child’s Perspective: Social mobility in Pandemic Times”