Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy released by Jean-Yves Duclos, the Federal Minister of Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, proposes to introduce legislation to establish an official poverty line for the country. This is an act of political courage, but the poverty line continually needs to be updated and improved.

Why is an official poverty line an act of political courage?

The statistical clarity announced in “Opportunity for all: Canada’s first poverty reduction strategy” is an act of political courage. Canada will have an official definition of poverty, and going forward Canadians will know exactly what politicians mean when they say the word “poverty.”

This is a historic first. No other Canadian federal government has been so definitive, and many countries do not have official poverty lines, though the United States does, a statistic dating back to 1964 when President Johnson declared a “war on poverty.”

What was the hold up?

Well, an official poverty line offers a clear measuring rod by which to judge success, much in the way that we evaluate Governors of the Bank of Canada according to a zero-inflation target, or Ministers of Finance by budget balances. Statistical clarity opens the possibility of holding our politicians to account for results, not just money spent: it puts the focus on outcomes, not just on process.

The risk of getting a failing grade has made many past politicians shy away from clear signposts.

The hesitancy runs even deeper because “poverty” is a statistic unlike any other: it is as much a value judgement to be made, as a hard fact to be observed.

Canadians have been down this road before, particularly during the 1990s in the aftermath of the all-party resolution committing the federal government to “seek to eliminate child poverty by the year 2000.”

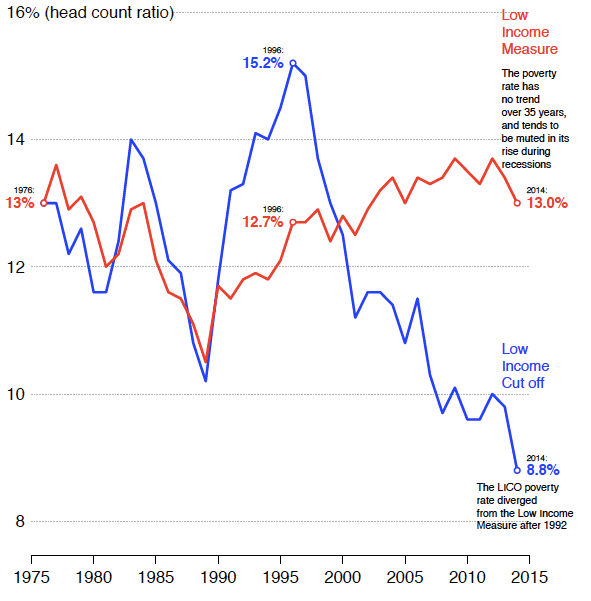

Politicians then punted the hard question about monitoring progress to the statisticians. And while many stakeholders and advocates then looked to Statistics Canada, this turned out to be more like a shopping trip than a policy evaluation: with the statistical agency putting two very different statistics on the table, cherry-picking was the order of the day.

The controversy as to whether poverty went up, down or sideways in Canada led the then Chief Statistician, Dr. Ivan Fellegi, to essentially scream “enough already.” Like a supreme court judge he punted the ball back to stakeholders, advocates, and politicians in a tersely worded public rebuke:

… poverty is intrinsically a question of social consensus, at a given point in time and in the context of a given country. Someone acceptably well off in terms of the standards in a developing country might well be considered desperately poor in Canada. And even within the same country, the outlook changes over time. A standard of living considered as acceptable in the previous century might well be viewed with abhorrence today.

It is through the political process that democratic societies achieve social consensus in domains that are intrinsically judgmental. The exercise of such value judgements is certainly not the proper role of Canada’s national statistical agency which prides itself on its objectivity, and whose credibility depends on the exercise of that objectivity.

… Once governments establish a definition, Statistics Canada will endeavour to estimate the number of people who are poor according to that definition. Certainly that is a task in line with its mandate and its objective approach. In the meantime, Statistics Canada does not and cannot measure the level of “poverty” in Canada.

Ever since no Statistics Canada employee utters the word poverty, always speaking of “low-income.” And ever since Canadians have not been able to have a healthy debate about what to do about poverty, arguing about numbers not policy.

To define “poverty” is to take a political stand: no ambiguity, no off-ramps, no U-turns possible. It is to be held to account, and that takes courage.

What is Canada’s Official Poverty Line?

A fall-out from the 1990s debate was setting public servants to work to devise yet another measure of poverty, oops … low-income, which became known as the “Market Basket Measure” because the method used to derive it involved costing out a basket of goods and services associated with a modest standard of consumption.

This is the statistic that Jean-Yves Duclos proposes to put into legislation as Canada’s Official Poverty Line.

Why did he choose it? Because it most closely reflects what those with lived experience of poverty told him about their challenges. Duclos spent a good deal of time just listening, …. well also traveling. His consultations involved numerous meetings, roundtables, and surveys, including a detailed portrait of poverty in six Canadian communities. Also his choice was validated by some existing and well executed provincial poverty reduction strategies, and by what some stakeholders and advisors suggested.

If defining poverty involves a value judgement, then in his view this definition comes closest to reflecting the needs, experiences, and challenges of those with lived experience of poverty. After all, those are the values that should be expressed.

His choice is meaningful and easy to communicate because it is based on the expenditures that people actually make in a way that is sensitive to regional differences.

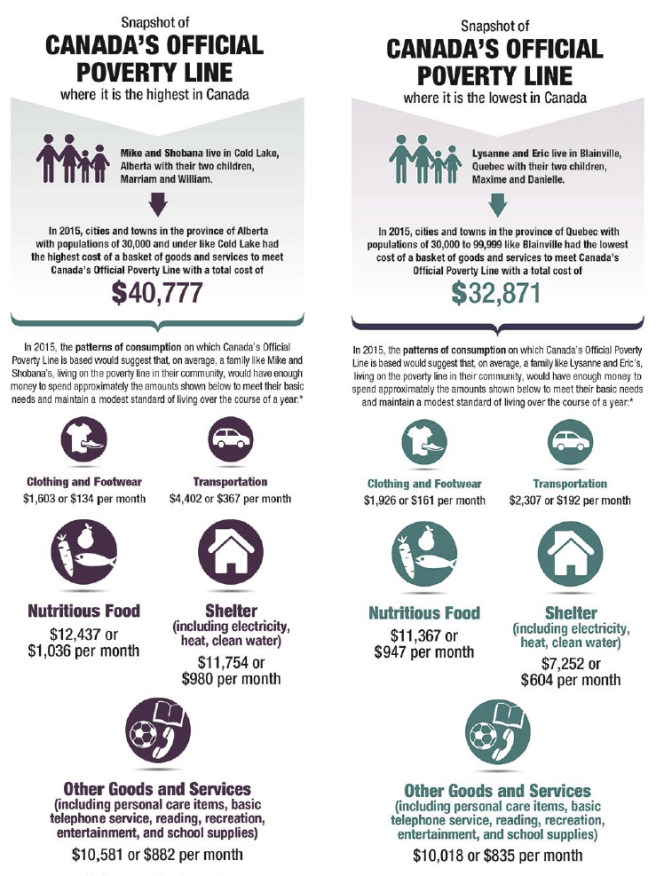

The current content of the basket is made up of four categories of goods and services—food, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation—and an “other goods and services” category.

The contents of this basket were originally established during the late 1990s and early 2000s to support social policy reforms at that time. Federal-provincial-territorial officials who reported to the Ministers responsible for social services were tasked with consulting and developing a basket of goods and services “representing a modest, basic standard of living.”

The basket refers to the basic goods and services appropriate for a typical family of four: two adults between 25 and 49 years, and two children, a 9 year old girl and a 13 year old boy. Statistics Canada determines the costs of these items in 50 regions that cover all of the provinces: 19 cities and towns, and 31 less densely populated provincial regions.

There are 50 poverty lines across the country, one for each of these communities, with the highest currently being almost $41,000 in parts of Alberta, and the lowest just under $33,000 in parts of Quebec, averaging $37,500. These expenditures are then adjusted for family size and extrapolated to all other Canadians. The poverty line for a person living on their own is half of the line for the reference family of four.

Statistics Canada then compares these costs to actual family incomes in each region to determine the number of Canadians not being able to afford them.

During 2015, 4.2 million Canadians, 12.1 percent of the population, did not have an annual income sufficient to prevent them from falling into poverty.

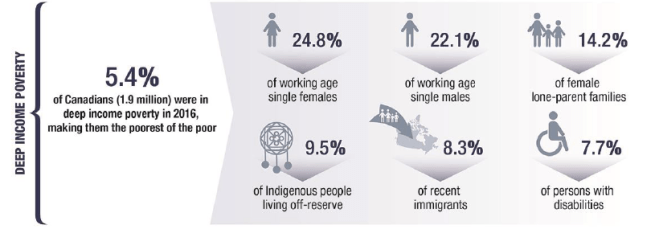

Duclos’s document also makes reference to “deep poverty,” which he defines as the number of Canadians with income below three-quarters of the official poverty line. This is used as one element in a dashboard of other indicators meant to reflect poverty of basic needs.

The Official Poverty Line is sensitive to the reality of being able to afford the necessities of life, but also sensitive to the reality of being able to afford a host of other things that permit full engagement in the community, things that presumably evolve with community standards.

This is what the “other goods and services” component of the basket is meant to represent. It introduces a “relative” component to the poverty measure. Deep poverty is based upon excluding this component, basing the calculation on just food, clothing and footwear, shelter, and transportation. In 2015 this amounted to 73 percent of the total, and offers the rationale for choosing three-quarters of the official line for the deep poverty line.

During 2015, 6.6 percent of Canadians lived in deep income poverty.

The contents of the basket have been updated once, and currently represent 2010 consumption patterns.

How can the Official Poverty Line be improved?

A regular updating of the basket of goods and services used to determine the Official Poverty Line is key to its relevance for public policy, and the Poverty Reduction Strategy commits to updating the contents every five years in a transparent and apolitical way.

Statistics Canada will have the independence and authority to conduct these updates, which are important because the needs and consumption patterns of Canadians continually change, as does the availability of specific goods and services and how they are distributed.

For example, the transportation component of original basket of goods included the cost of using and maintaining a five-year old Chevrolet Cavalier in communities without public transit, but a new car had to be identified during the 2010 update as General Motors stopped manufacturing this model.

Just as importantly, what it takes to participate normally in society evolves.

The “other goods and services” category, for example, includes basic telephone service, but not cell phones or access to the internet.

The last review determined whether or not to include an item in this category by posing two questions: Do 70 percent or more of families nationally, and in seven of the ten provinces with at least two-thirds of the population, purchase the item? Do the items contribute to social and economic inclusion and to a modest but basic standard of living that in some way is not accounted for by the existing basket? This rules-based approach should be continued in the proposed regular five-year updates of the official poverty line.

Regular updates of the basket are vital to the relevance of the official poverty line, but there are also more fundamental limitations hard-wired into the statistic that need to be reconsidered.

The Official Poverty Line is currently derived from a survey conducted by Statistics Canada called the Canadian Income Survey. In 2015 it was administered to 27,119 households and 63,197 individuals.

All statistics from surveys are subject to a certain amount of uncertainty. In this case, Statistics Canada estimates that a band of about 0.3 on either side of the national poverty rate would imply a two-thirds chance of encompassing the actual poverty rate, and a band twice as large would imply a 95 percent chance.

The Poverty Reduction Strategy commits to funding Statistics Canada to increase the sample size of the survey in the hope of narrowing this band, and in this way increasing the accuracy of the information, particularly when studying poverty among particular groups: for example, by gender, region, or living arrangements.

But more fundamental improvements dealing with the scope of the survey are also important.

Statistics Canada will have to determine if the consumption basket is appropriate for all Canadians since public policy has shifted from a focus on child poverty to poverty in general. As I mentioned, the Official Poverty Line is based on the basic goods and services appropriate for a family of four: two adults between 25 and 49 years, and two children, a 9 year old girl and a 13 year old boy. The expenditures patterns for this family type are then adjusted for family size and extrapolated to all other Canadians.

But it is not clear whether or not the consumption patterns of this reference group are appropriate for older people, or people living on their own.

Furthermore, Duclos’s document quite rightly devotes a full chapter to “Working with Indigenous Peoples”, and certainly if there is a national priority for a poverty reduction strategy, it must in some meaningful way address poverty on reserves. But Statistics Canada surveys are not conducted on reserves, nor in the north. So the areas of the country in which poverty is probably a big issue make no appearance in the data.

Monitoring progress with the official poverty line is limited not just by which population groups are covered or left out of the survey, but also by its timeliness. Statistics Canada has a significant lag built into the survey because it obtains information on individual and family incomes from income tax information, and links these tax data to the host of questions that survey respondents answer.

This is done to reduce respondent burden, and presumably to obtain more accurate information, but it does mean that complete income tax data are not transferred to the statistical agency for many months after the survey reference year has ended.

For example, the 2015 poverty rates were released on May 26, 2017, almost 18 months after the reference year ended. Statistics Canada has worked to cut this delay, releasing the 2016 poverty rates on March 13, 2018, about 15 months after the reference year. But this is still much longer than what Canadians were accustomed to when the survey was entirely questionnaire based and did not rely on administrative data, which generally lagged the reference year by six months.

Timeliness is an important part of data quality, particularly now that public policy is inviting Canadians to monitor progress with official statistics.

[ I was the Economist in Residence at Employment and Social Development Canada during the 2017 calendar year, working in the Deputy Minister’s office as a member of the team of public servants helping to develop Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy. During 2018 I continued to serve as a part-time advisor in the Deputy Minister’s office on this and other files. Though this post draws closely from my reading of Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy, the views expressed are entirely my own, and in particular should not be interpreted as reflecting the positions of Employment and Social Development Canada, nor of the Minister and his staff. ]

Congrats on the PRS Miles. A long time in the making and a historic announcement. Now the real fun begins!

My goal in coming to this site was to see where I fell in the bracket of poverty. I fall well below with getting Canada disability and wbc.. ie i get just over 13,000 a Year. So I definitly do not get enough to live on with a disability pension, how do we fit into the picture? Is the Government going to give us more money? I somehow doubt that. During all of the COVID mess us pensioners were the ones that received the least help.

I’m a 71 year old senior citizen living the Suburbs of the GTA, east of Toronto. My goal in coming to this site, along with searching median income, was to determine where my yearly gross income, of $20,561.00 for 2018, falls with regard to the average Canadian. I appreciate the effort that went into this post. While not definitive, it does give me a handle to further explore. Thank you for your service and work in producing this post. Live long and prosper 🙂 dc

Thank you for your feedback. You can get more detail on Canadian median incomes by exploring the Statistics Canada website. Here is one link that might be helpful https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110001201 . Use the “Add/Remove” data tab to get more or less information, for example the information is available for those older than 65 years of age.

My family of 4 fits the statistic perfectly but the basket projections for cost of living don’t even touch the rates that we experience in northern Alberta. With high rates of housing the basic rent accounted for is half of what most families pay. Oil field jobs have driven up rates and made housing unavailable. The increase in minimum wage and carbon tax levies only drove up the cost of food and clothing. For most two income households it’s those of us who sit just above poverty lines that struggle and there is no sliding scale for aid. We have now seen a decrease in women going back to work because of the high cost of childcare. Alternatively they will be suplimented by the government for having children and not working. I know a few single mothers who make more money through welfare and tax benefits than I do working full time.

Interesting article.

I am 60 now, and forcibly retired since the age of 56 (ironically because of government of Canada actions that has labeled me a threat to public safety solely based on 4 email messages that were coarsely worded but in no way threatening)

Spent my life working hard, lived through 3 bankruptcies as an employee, one massive layoff with zero chance of recall, and one situation of pervasive temporary layoffs. All the while paying rather high Canadian taxes, so all things considered, many in this country do not even stand a chance at accumulating wealth and taking care of themselves, even someone like me who was a professional making OK but not great income.

Great shame that no one in this country will put their pants on and acknowledge the structural design of the state actually contributes to poverty.

No matter how educated, hard working, and diligent, and fiscally responsable I was, getting back up after being seriously knocked down, I am now facing poverty in the face.

Canada typically puts on the unfortunate hypocritical face of how good and great a society they are. Far from the truth of reality.

$20,400 is shown as the max. poverty level for a single adult living alone. How can one survive on this meagre amount? Rental accommodation (at a minimum) cannot be less than about $750/month (or $9,000/year), leaving $11,400 for everything else: food, clothing, footwear, travel expense (car/bus/train, etc.), entertainment, telephone, and sundries. This is scary stuff!

I don’t understand how the maximum CPP can be $13,850 per year.

I know my comment will only fit into a fairly small category of people, but the issue of food shortages, I can not help but notice not one mention of a food plot, even a few potatoes. It seems there should be a greater emphasise on self sufficiency. I assume a back lash on this comment based on ‘where to find the time’ , or an ‘available space.’ In tisdale saskachewan there is an abundance of great land that will grow a decent garden. You have probable heard the saying teach someone to fish. The point is to gain improvement in life by using resources at hand if possible.

No mention of Canada’s seniors couple like us in our mid 70’s with an Old Age Pension total of $1,300 a month which is a joke and one individual CPP of $483 a month since working from 1963 another joke. This country has the means and budget to seriously provide a decent monthly income for those folks who worked their lives always paying taxes and seen it all given away to other countries instead of looking after Canada first. This country is seriously in debt not because of social programs or because of infrastructure upkeep but because of mindless spending.

You need to apply for the federal GIS (Guaranteed Income Supplement) which is a supplement for low income seniors, and also look into what money might be available to low income seniors in your province.