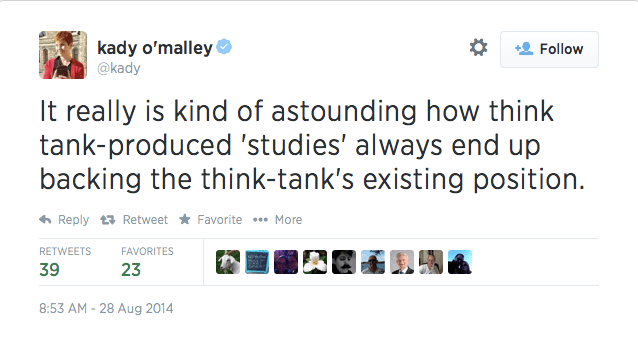

The Fraser Institute has weighed in on the income inequality debate with a report called “Income inequality: measurement sensitivities” that reviews the statistical measurement of income inequality in Canada.

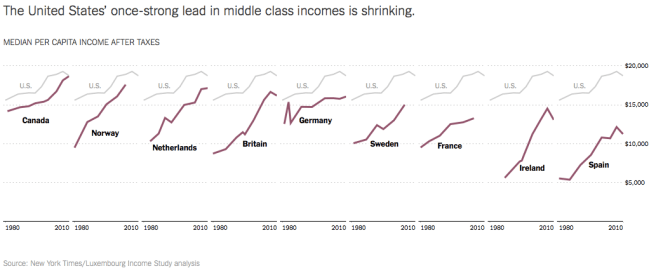

The report quite rightly points out that there are many nuances in the measurement of income, and income inequality, and that the results vary substantially depending upon how economists and statisticians deal with them. Is income measured by earnings, or by total income that includes not just business and investment income but also government transfers? Should it be measured before or after taxes? And should we be looking at total family income or try to represent this as individual income by accounting for family size?

The analysis is carefully done and clearly presented, and though it covers ground that is pretty well standard for many economists working in this area, it helps to clarify the issues for a broader audience.

But the study concludes, in the words of the screaming press release, that there is “No income inequality crisis in Canada when it’s properly measured.”

That is the wrong inference to be making. What the study is missing is a coherent understanding of the link the different measures it so accurately calculates. As a result it misses important policy lessons.

Continue reading “Inequality may be complex, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make sense of it”