[ This post is based on the opening address I gave on the invitation of the New Zealand Treasury to the “A More Inclusive New Zealand Forum” held in Wellington, New Zealand on July 27th, 2015. ]

I would like to open this gathering with a statement of admiration for both its content, and its process. The organizers have asked us to deliberate on “inclusion”, and to do so through conversation.

As a part of my contribution to this conversation I would ask you to consider four major messages, all four of which revolve around the question: What does inclusion mean?

I use “mean” in the sense of how we define inclusion, and “mean” in the sense of its implications for policy.

What does “inclusion” mean, and how can we give it enough precision to inform public policy?

My four messages are:

- an inclusive society means that all children can become all that they can be;

- an inclusive society seeks to eliminate child poverty;

- income inequality has the potential to erode inclusion;

- public policy must address many dimensions of inequality.

1. Children can become all that they can be

“Social inclusion” is a slippery term, and it certainly does not have a distinct meaning in the social sciences in a way that at least I, as an economist, would feel comfortable drawing implications for public policy.

It helps me to reflect on another term that is sometimes also used to frame public policy: “assimilation”.

For example, assimilation is used in some countries to refer to policies addressed to immigrants. It frames policy discourse in a way that leads to a focus on the shortcomings of migrants. There is a sense of a clear and distinct “mainstream” to society, or to the economy, and migrants are lacking in the skills, language, or even in the attitudes, religion, and culture necessary to fit into this mainstream. They need to change.

This is overtly clear in the way that some extreme groups argue against the very presence of migrants, or accommodations toward them. If this perspective rubs many of us the wrong way it is because at some level we recoil from the underlying assumption of “assimilation”: that the mainstream is clear, fixed, socially preferred; that the task for groups defined as the “other”—be they migrants, those with low-income or without work, those with physical or mental disabilities, or those of colour—is to adjust, to adapt, to assimilate, and indeed to ultimately identify with that mainstream.

It surely does not take much second thought to recognize that barriers to assimilation may be structural, reflecting overt discrimination in access to fundamental resources that are the basis for full participation in society: access to education, health care, income security, and even to jobs for which migrants may well be perfectly qualified but never hired because of skin colour, accent, or simply the spelling of their last names.

In other words, if perspectives like this rub many of us the wrong way it is because we believe there is a reciprocal obligation, something to be negotiated, something reflecting a partnership in the building of society in which all parties are treated with equal respect, and are in turn changed by the relationship.

This has to be at the core of what we mean by “inclusion” if it is to be a helpful framework. Inclusion embodies the idea that identity is something to be continually re-negotiated as successive waves of minority groups enter into conversation with the majority.

So in this way conversation is not just an excellent metaphor for the meaning of inclusion, it is also a vital mechanism to achieve it. It is through conversation that we can respectfully negotiate the terms of a partnership, but at the same time we appreciate conversation for its own sake, are not threatened or dissatisfied by the fact that it is open-ended, indeed this is what reassures and enriches.

But if building an inclusive society through conversation is to be sincere and productive, it has to be done between partners who demonstrate mutual respect, and be capable of freely engaging; partners with a clear sense of others, but also of themselves. It seems to me that this sort of capacity or capability is also at the core of what we mean by “inclusion”.

The idea of capability that I have in mind is rooted in the thinking of Amartya Sen, the Harvard University economist who for a considerable time was based at Cambridge University. Sen argues that we should live in a society in which we all have the freedom to choose the lives that we value. This vision of the social good certainly puts to one side the notion of assimilation, of identifying with a fixed mainstream.

An important prerequisite of this sort of freedom is having a fully developed sense of self, of capacities to define what we value, and to make the choices necessary to get us there.

When thinking in these terms it is natural to focus upon children. Certainly this is not the only way to think about Sen’s ideas, but I have to admit to being surprised that there is so little mention of children in Professor Sen’s amazing book Development as Freedom.

I would like to put the focus on children, and suggest that if a society is inclusive, it is in the very least a society in which children can become all that they can be.

Obviously this is not the only dimension, and part of the task facing you is to clarify other dimensions through your conversations. But focusing on children allows me to illustrate a framework for understanding the underlying drivers of inclusion, of the challenges facing societies seeking to be more inclusive, and of some public policy implications.

My definition implies that family background should not be destiny, that place and position in society should not echo excessively across the generations with today’s poor families raising children who will grow up to be the next generation of poor adults, or for that matter with today’s rich families raising the next generation of rich adults.

2. An inclusive society seeks to eliminate child poverty

It would help in explaining my second major message if you had an appreciation of my taste in music.

Many of you will recognize this women.

This, of course, is Shania Twain, the country-pop musical sensation, whose albums outsold all other performers throughout the entire world during the mid to late 1990s. Ms. Twain is an entertainment superstar whose career was launched in Nashville Tennessee, and who rode a wave of what was then a relatively new technology in the distribution and sale of music, the compact disc.

As a result she became very wealthy. Among other things she owns a beautiful home on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland and, according to her autobiography, was at one point building a dream home somewhere in New Zealand.

But she also owns a relatively modest summer cottage near Timmins, in the Canadian province of Ontario, where she grew up (and incidentally not so far from where I was born). While Ms. Twain stands at the top of her profession and likely has enough money to put her in the global 1%, she started life, it would be charitable to say, in very challenging circumstances.

She is one of five children who had three different biological fathers. Her mother would appear to have suffered from depression, and the main father-figure in her life was her stepfather, a member of a first nations community in Northern Ontario, who at a young age left his community and faced many challenges in his partnership and the raising of five children.

Ms. Twain describes a childhood of repeated moves between towns, rented apartments, and schools, as the family continually struggled to make a living. One of her homes was nothing more than a couple of basement rooms with a dirt floor. Hers was a life of relentless, persistent poverty; a poverty that stretched the very fabric of her family causing stress, uncertainty, and even physical and emotional abuse.

A poverty that she says was just unnecessary.

And while we can applaud the energies, motivation, and innate talent that ultimately led to her success—a movement from the very bottom of the socio-economic ladder in a small Canadian town to the very top in the world—we should also recognize that her story is clearly rare. How many children raised in similar circumstances have fallen by the wayside, and never developed their full potential, however, more modest than global stardom?

A commitment to eliminating child poverty is a conversation worth having.

In this conversation it is also important to be clear about the type of poverty we have in mind. Ms. Twain’s childhood, I think, underscores that two important dimensions are worth keeping in mind.

Obviously enough the first relates to basic needs and necessities—adequate resources to be able to procure food, shelter, and clothing.

But if we are to take the idea of inclusion as capability development seriously, a second dimension is just as important and relates to relative deprivation—adequate resources to participate normally in society. A cell phone may have been considered a luxury a decade or more ago, but for the present day teenager it is a necessity.

Amartya Sen underscores this dual nature of poverty. If children are to become all that they can be, then they have a need for a certain relative standing in our communities, a standard of living that not only allows them to be feed, sheltered and clothed, but to also participate fully in the society in which they are growing up.

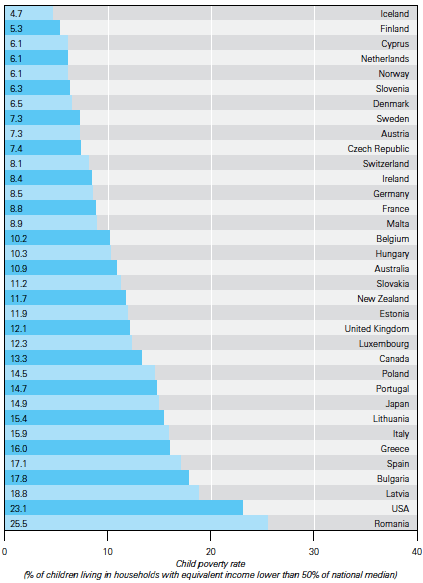

To give this idea public policy traction I suggest that we think of a family falling into poverty if it has less than half the resources of a family half way up the socio-economic ladder. In thinking of income poverty this would mean setting a poverty line at 50% of the median income appropriately adjusted for family size. It would also mean regularly updating this poverty line to reflect economic and social changes.

A society that seeks to eliminate child poverty might consider making a commitment of the following sort. Each government would commit to lowering child poverty below the level it inherited at the start of its mandate. This target would be defined as the poverty rate according to one-half of the median income in the year it assumed power.

Successive governments would face a similar commitment, but based upon a new poverty rate, that defined according to the new median income in the year it assumed power. In this way the poverty line would be continually updated as the median income changes, a reflection of the evolution in what it takes to participate normally.

3. Income inequality has the potential to erode inclusion

All of this suggests that when our goal is more social inclusion a discussion about poverty cannot be divorced from a discussion of inequality.

A conversation about poverty is a conversation about inequality in the lower half of the income distribution, and it makes the plight of the relatively poor a social concern. In this way more inequality in the lower half of the income distribution has the potential to erode inclusion.

But in presenting my third major message I would like to suggest that income inequality throughout the entire income distribution also has this potential.

Ms. Twain’s story is compelling because she was able to escape a history of poverty, and offer for her children a future of plenty. This movement, both up and down the income distribution, without regard to family background is termed social mobility. If money matters, a more inclusive society—a society in which children can become all that they can be—will be a society in which the circumstances of birth matter less.

Income inequality has the potential to erode inclusion because it puts social mobility at risk. Here is a ranking of some rich countries according to one measure of social mobility: the extent to which the adult incomes of sons are related to the incomes of their fathers. This degree of stickiness between parent and child incomes varies across the rich countries, with almost one-half of income inequality in one generation being passed on between fathers and sons in the UK, Italy, and the United States, but less than one-fifth in Finland, Norway, and Denmark. New Zealand occupies a middling rank in this league table along with countries like Australia and Canada.

While intergenerational income mobility varies, it varies in a particular way. The greater the level of income inequality a generation ago, the lower the degree of mobility—that is the greater the chances that a child will occupy the same place in the income distribution as his or her parents. Greater inequality, in other words, tilts the playing field making it harder for children of lower socio-economic status to climb the ladder, and also more likely for those of higher status to inherit high status in their turn.

This is relationship is often referred to as the Great Gatsby Curve, a name coined by Alan Krueger, the Princeton University professor, when he served as President Obama’s chief economic adviser. The Great Gatsby Curve raises a caution for our conversation about social inclusion. It suggests that the capacity to become all that you can be, will be more likely in more equal societies. To the extent that family income matters for life chances then the more unequal an economy, the less likely children will escape their family origins.

Income inequality, in other words, has the potential to erode social inclusion.

4. Public policy must address many dimensions of inequality

I have put the focus on differences in income, both in thinking about poverty and inequality. But as important as income is, it is not the only driver.

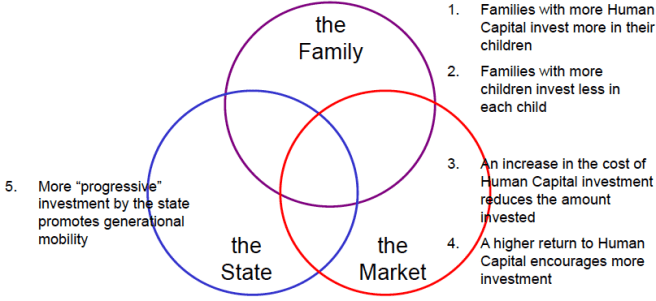

A child’s life chances are determined not just by inequality of money, but inequality of education and health care, inequality of experience and expectation, inequality of motivation and esteem, inequality of support and connections. So to fully appreciate the policy challenges it is important to appreciate that the underlying drivers of poverty, social mobility, and ultimately of capabilities and inclusion relate to the interaction between three important forces determining a child’s development: government policy, families, and labour markets.

We should never underestimate the major influence that families have on the well-being and development of children. But families must interact with the labour market, and rely on social policy for support and insurance. All children will be more likely to become all that they can be if their families have access to high quality care during their early years, access to high quality education from primary school to university, and access to health care throughout their lives.

Public policy plays an important role in complementing the efforts of families, and will contribute to social mobility if it is progressive, of relatively more advantage to the relatively disadvantaged.

Let me offer two stories drawn from my own country to illustrate both a major failure and a major success in building an inclusive society.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada recently held a major event to mark some of its work in documenting the consequences of the Residential School system, which it describes on its website by saying that:

For more than 120 years, tens of thousands of Aboriginal children were sent to Indian Residential Schools funded by the federal government and run by the churches. They were taken from their families and communities in order to be stripped of language, cultural identity and traditions. Canada’s attempt to wipe out Aboriginal cultures failed. But it left an urgent need for reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples.

This policy, conducted in the name of assimilation, has left many scars among parents who lost their children, and scars among their children and grandchildren. Families have yet to fully recover. This is an extreme historical example of just what it means not to build a more inclusive society.

It seems to me that the conversation between Canada’s first nations and the majority is not on as strong a footing as their counterparts in New Zealand, reflecting in part a very different context that contributes to a less than mutually respectful conversation: a population that makes up no more than about 3 to 4% of the country’s total, a population that is geographically dispersed with many different cultures and languages, and a treaty process that is much more complicated and not constitutionally entrenched.

On the other hand, the experience of many Canadian immigrants offers a positive lesson, underscoring both the importance of family and of social institutions in promoting the capabilities and social mobility of children. There is not doubt that in recent decades many immigrants pay a significant cost in migrating to the country, experiencing lower earnings and a slower growth of earnings than in the past. Many come for the sake of their children, investing a great deal in them both in monetary and non-monetary terms.

The Canadian education system also seems to have complemented these efforts. Most young children of immigrants, particularly those from families in which the home language is not English or French start primary school at a significant disadvantage with much lower reading tests scores than their Canadian born counterparts with Canadian born parents. But by the end of primary school this gap is closed. Indeed, some immigrant groups and second-generation Canadians turn out to be the most educated groups in the country.

Social mobility is a reality in part because social institutions and public policy have complemented the efforts of these families in very important ways.

A “more” inclusive society

This conference has asked us to engage in a conversation that is not about building a fully inclusive society. That, I think, would be asking too much, because inclusion is ultimately based upon an open-ended conversation. Rather, it has asked us to engage in a conversation about building a more inclusive society than we currently have. And to do so I have suggested that we need to accept a definition of inclusion that refers to the full development of the capacities of children so that they are in a position as adults to live the lives that they choose to value.

In this sense we might do well to recall the words of R. H. Tawney, the famous British historian. Tawney was also concerned about the same issues, and offered us good advice when he wrote:

It may well be the case that capricious inequalities are in some measure inevitable, in the sense that, like crime and disease, they are a malady which the most rigorous precautions cannot wholly overcome. But, when crime is known as crime, and disease as disease, the ravages of both are circumscribed by the mere fact that they are recognized for what they are, and described by their proper names, not by flattering euphemisms. And a society which is convinced that inequality is an evil need not be alarmed because the evil is one which cannot wholly be subdued. In recognizing the poison it will have armed itself with an antidote. It will have deprived inequality of its sting by stripping it of its esteem.

— R.H. Tawney (1964), Equality, Fourth Edition, page 56.

[ You can download the slides that accompanied my presentation by clicking on this link. ]

The book ‘The Son Also Rises’ by Gregory Clark basically paints a dim pitcture that social mobility is not real or rahter there is a strong correlation between a persons wealth and the wealth of their forefathers. A study was conducted with familes five generations apart (in the last 150 years) and the results were similiar even in countries which are perceived to be more equal e.g. Sweden. If ture, this is worryng because during this time period we have seen the devastation of world wars and various socialist movments which could have flattened inequality. It may not be suffificient for governments to provide counter balances, our attitudes may also need to change.

Thanks for drawing our attention to Clark’s book. You might have an interest in reading this post, which reviews the book and addresses the very issues you rightly raise: https://milescorak.com/2014/05/22/social-mobility-fixed-forever-gregory-clarks-the-son-also-rises-is-a-book-of-scholarship-and-of-scholastic-overreach/

thanks, Miles