The Canada Child Benefit offers a policy option that the United States should consider in pursuing a goal to reduce child poverty by half.

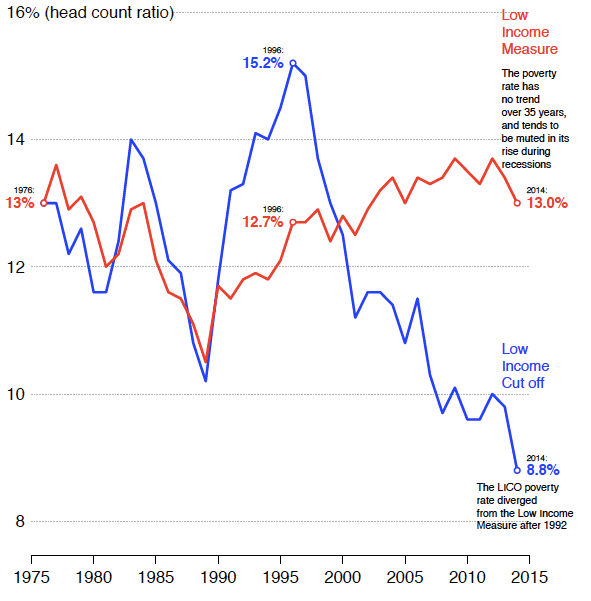

The commitment to address child poverty has waxed and waned in Canada since an all-party resolution was passed in the House of Commons in late 1989 committing the federal government to “seek to eliminate child poverty by the year 2000.”

Poverty and social policy are now high on the agenda of the current federal government, which intends—over the course of the next six months—to articulate a poverty reduction strategy, but which has already taken a major step toward this goal by introducing the “Canada Child Benefit” in its first budget. This program came into effect in July 2016, and represents a major revamping of cash support to families with children.

The Canada Child Benefit represents an important improvement in the incomes of families with children, the government forecasting that by the end of its first full year of operation in 2017 the program would almost halve the number of children in poverty from the level prevailing in 2013. This innovation merits attention from policy makers in the United States and other countries.

I made a presentation to the “The Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years” of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

The program of the June 20th public information gathering included presentations from eight experts. I was the only participant from outside of the United States. Download the slides of my presentation: Presentation-Corak-National-Academy-Sciences-Engineering-Medicine-Child-Poverty.

It was based on a background report I prepared for the committee, which you can also download: Text-Corak-National-Academy-Sciences-Engineering-Medicine-Child-Poverty. The report details the nature of the program, compares it to the programs it replaced, and offers links to additional resources helpful in simulating the impact a similar design could have in other countries.