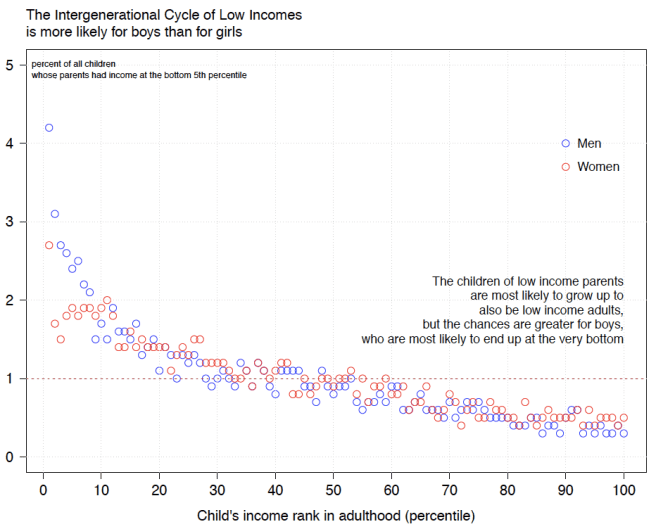

Children of low-income parents are more likely than not to grow up to be low-income adults. This is true for both boys and girls, but more so for boys.

This figure shows the rankings of children from low-income Canadian families, what fraction stand on each of the 100 rungs defined to equally divide the population across their adult income distribution. Their parents stood on exactly the bottom 5th rung of their income ladder, and the likelihood of them not advancing very much or even falling lower is clearly evident.

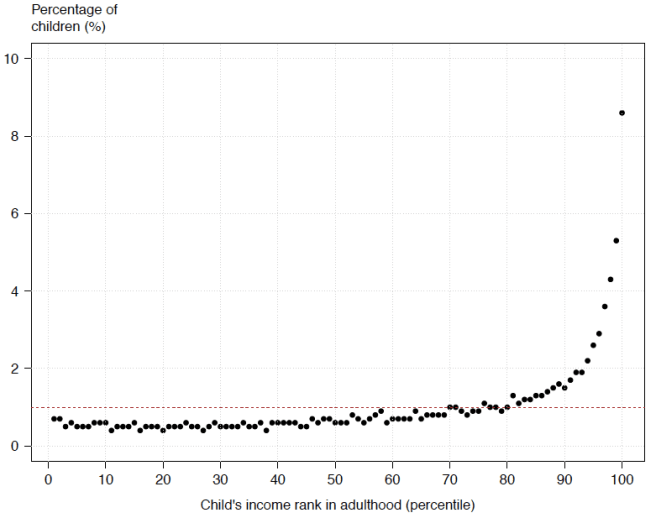

If adult incomes were completely independent of family income background, then we would expect 1 percent of these children to be on each of the 100 divisions of their income distribution. If this were the case children of low-ranking parents would be as likely to rise to middle incomes, or even to the very top, as they would be to stay on the same rung as their parents, or fall lower.

But in fact, this cohort of Canadians (those born in the 1960s) are much more likely to be the low-ranking adults of the next generation and are more likely to repeat the experiences of their parents.

This inter-generational cycle of low-income is more likely for boys. Although there is considerable upward rank mobility among these children, men raised by parents who were outranked by 95 percent of their counterparts are most likely to fall even lower, to be outranked by 99 percent of their cohort. Their chances of falling to the bottom 1 percent are more than 4 percent.

They are most likely to remain in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution. Although an intergenerational cycle of low-income is also the most likely outcome for women, the chances are significantly lower, hovering in the neighbourhood of 2 percent for each of the rungs up to about the 10th.

[ This post is an edited excerpt from a forthcoming paper I have written called “‘Inequality is the root of social evil,’ or maybe not? Two stories about inequality and public policy”, which is published in the December 2016 issue of Canadian Public Policy. If you have any feedback please feel free to let me know in the comments section. ]