Every Statistics Canada data release on the share of the economic pie going to the top 1% elicits strong opinions, the most recent being no exception. Do top earners elicit rather dishonourable sentiments such as envy that should be given little weight? Or do they challenge our need for community and inclusion, influencing the way we live our lives in more fundamental ways? Should we praise the top 1% or worry about them?

It depends. We would be in a better position to answer this question if we put aside questions of merit and just deserts and focused more on the sources of social mobility and the capacity to conduct policy to support it in an era of higher inequality.

Earnings mobility for children from the very broad middle—parents whose income ranges from the bottom 10 percent all the way to the cusp of the top 10 percent—is not tied strongly to family income. These children tend to move up or down the income distribution without regard to their starting point in life. This may be one element of insecurity among the middle class: in spite of their best efforts, their children may be as likely to lose ground and fall in the income distribution as they are to rise.

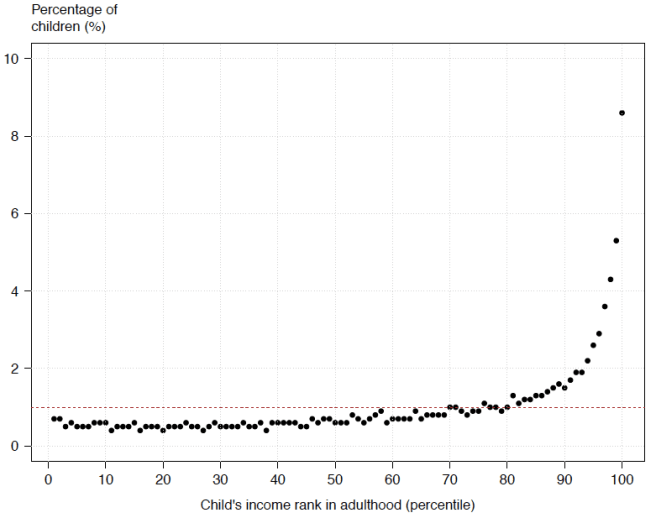

The situation is very different for children raised by top-earning parents, as the above figure illustrates. It shows the intergenerational cycle of privilege, the percentile rank in adulthood of children raised by top-1-percent parents. This playing field is clearly not level. If it were, all the points in the figure would be the same, all lining up along the dashed horizontal line drawn for reference at 1 percent.

The most likely adult outcome of the children of top earners is to also be in the top 1 percent, and they are disproportionately unlikely to fall below the top fifth. Some of the sources of this intergenerational stickiness in top incomes may not be seen as fair, and it may even be perceived to present a barrier to upward mobility for the children of the majority.

For example, the most common way to find a job is through family and friends. That holds true for all of us, but it is immensely more likely for the kids of the very rich. About 40 percent of young Canadian men have at some point worked for exactly the same firm that at some point also employed their fathers.

But if dad’s earnings put him in the top 25 percent, these chances are above average; they start taking off if dad is in the top 5 percent and are higher still for top earners. Almost 7 out of 10 sons of top-1-percent fathers had a job with an employer that had also employed their fathers. All parents want to help their children in whatever way they can. However, top earners can do it more than others, and with more consequence: virtually guaranteeing, if not a lifetime of high earnings, at least a good start in life.

Connections matter. And for the top earners this might even be nepotism. This is not a bad thing if parents pass on real skills to their children, skills that might be specific to particular occupations, industries, or even firms. If this is the case, then it makes economic sense to follow in your father’s footsteps.

Wayne Gretzky often talked about the role his father played in developing his skating and stick handling skills. He spent hours and hours with his father on the backyard rink. But not all top earners got to where they are because of this sort of investment. In fact, sons of top-earning fathers who do not work at the same employer as their fathers are much more likely to fall out of the top than those who do.

Bad nepotism promotes people above their abilities by virtue of connections, and it erodes rather than enhances economic productivity. Richard Reeves of the Brookings Institution encapsulates this intuition when he speaks of a “glass floor” supporting untalented rich kids, a floor that at the same time limits the degree of upward mobility for others.

There is, however, an even larger cost. Social mobility is about a lot more than just using job contacts to make it into the top 1 percent. It is also about making investments in the health, education, and opportunities of all children and supporting families in a way that complements their efforts to promote the well-being of their kids. If the rich leverage economic power to exercise political power, they can also skew broader public policy choices—from the tax system to the education system, and other sources of human capital investment—in a way that limits possibilities for the majority.

Social mobility is turned into a race, a race through a course with many bottlenecks that the relatively advantaged are best at manoeuvring. Besides, all of this discussion refers simply to the correlation of earnings across generations, which is only a partial measure of mobility. The inheritance of material wealth, not just earnings advantage, should also be part of the way we measure and think about social mobility. Much higher incomes at the top over an extended period translate to a higher stock of wealth, and this may advantage the next generation in a way that is not tied to their earnings capacity.

All of this may start eroding the belief that labour markets are fair and that anyone can aspire to the top. It is not envy that is at the root of a connection between the well-being of the less rich and the rich, but rather a concern over fairness as equality of opportunity. If the rich cannot leverage economic power to exercise political power, then it is quite possible for the majority to live with a richer top 1 percent and be less concerned about how this minority will influence their welfare and the prospects of their children.

[ This post is an edited excerpt from a forthcoming paper I have written called ” ‘Inequality is the root of social evil,’ or maybe not? Two stories about inequality and public policy”, which is published in the December 2016 issue of Canadian Public Policy. If you have any feedback please feel free to submit your input in the comments section. ]

HI Miles,

When I read this bit:

“This may be one element of insecurity among the middle class: in spite of their best efforts, their children may be as likely to lose ground and fall in the income distribution as they are to rise.”

I thought “but that’s essential to income mobility; I can earn more than my father while keeping the same position if everyone else rises, but if I rise to a new rank, someone else must have fallen in relative terms.”

However, I found this bit from another recent post of yours:

“This is what sticks in the throat about the rise in inequality: the knowledge that the more unequal our societies become, the more we all become prisoners of that inequality. The well-off feel that they must strain to prevent their children from slipping down the income ladder. The poor see the best schools, colleges, even art clubs and ballet classes, disappearing behind a wall of fees or unaffordable housing.” (quote from FT)

So as society becomes more unequal, parents fear downward relative mobility more. The gaps between the rungs of the ladder are bigger. Downward relative mobility in a relatively equal society with a decent life for the worst off may not be a big deal. Also if incomes are rising it may not a big deal. But if we aren’t seeing absolute increases, *and* inequality is increasing, then parents start to get worried, and start to behave in more competitive ways. They struggle to make sure their kids get ahead, they make sacrifices. And then (maybe) they don’t support progressive policies that might give other kids what they struggled to give theirs.

Yes I agree Andrew, particularly with how you have phrased it in your last paragraph. This would imply that both absolute and relative mobility are important. If we promote mobility, there are going to be costs for some and this will be much harder to accept if at the same time inclusive economic growth has slowed and the degree of absolute mobility has fallen.

Let me give you another angel on this. At the age of 11, and my sister 6, my mother, 33, divorced my father, 1964, and got a judgement of ‘Mental Cruelty’, mostly for my a$$hole father being a serial home-breaker. I was living in wealthy suburban Connecticut, in a big house and a superior school system. Coming home from camp, I found myself dumped into an urban apartment, and an inner city school, headed by a single parent household. Three months later, I met my father’s future wife, he was 43 and she was 20 years old, and was married just short of the 5th anniversary of the divorce, and had 2 quick children. My sister and I always financially struggled, while the next two children grew up solidly upper middle class, and are millionaires, today. For decades my father mentally abused me complaining about my mother and her family, and how broke he was. His most favorite thing he would say to me is “I’m broke, I’m poor, I don’t have a pot to piss in, your mother, her mother, her sister, the lawyers, the judges, they all broke me”, and I would here this dribble as his newer family are being brought up in style. At age 59 1/2 I was diagnosed on the autism scale, while my father’s final words too me were ‘You are the black sheep of the family’, as his wife was standing there. My a$$hole father died with a $5M estate, with 98% going to the newer family, and not so much as a dollar in sight for my sister and me. Talk about children being put on the down escalator.

Miles , the top 1 % is certainly of interest. What is the gender breakdown and how has it changed over the last decade. Median age will be important as some may be in the peak of their earning years. What is the role of human capital in placing them in that position, or the role of inherited capital. Are their incomes related to their contribution to society or are they earning incomes based on rents that they are able to appropriate? How many were raised in two parent households? What was the income / education levels of the mothers of these children. What is the median IQ of each member? What percentage can be classed as minorities? What percentage of their income was derived from Dividend / investment income, thus indicating the benefits of a high saving rates . Answers to these questions will in my mind indicate whether the top 1 % got there more by connections or favorable environment or by own effort. I am genuinely happy for the top 1 % if they got there by own effort. I am however more concerned by the bottom 1% … the poorest in society. Are they there because their parents were there. Is poverty inherited? If so how could we lose this inheritance. This for me is the other side of the equation and the more interesting one.