Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley has updated his work with Thomas PIketty on the evolution of US Top Incomes to 2010.

He finds that:

“In 2010, average real income per family grew by 2.3% … but the gains were very uneven. Top 1% incomes grew by 11.6%, while bottom 99% incomes grew only by 0.2%. Hence, the top 1% captured 93% of the income gains in the first year of recovery. Such an uneven recovery can help explain the recent public demonstrations against inequality.”

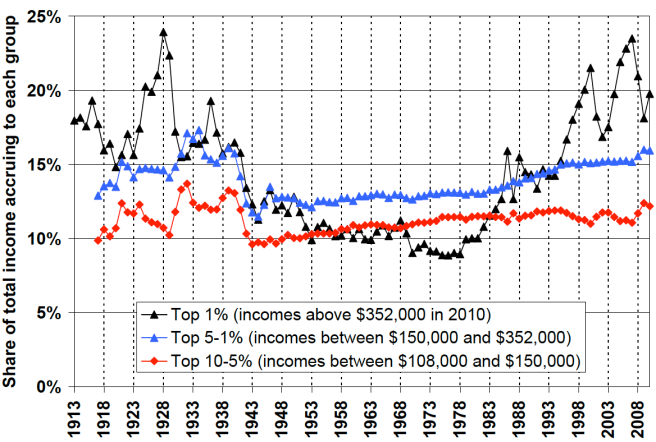

The 10 page update offers a clear picture of how income shares have varied over different business cycles, as well as the long-term trends since 1917. Top income shares fell dramatically after World War II, stayed flat, then began to rise in the early 1980s and have returned to their pre-War levels.

The top 10% in the US take now take home about 47% of all income, but this is driven by the top 1% who account for 20%.

The difference between the business cycle of the 1990s and the 2000s is that the incomes of the bottom 99% grew by 20% between 1993 and 2000, but only by 6.8% between 2002 and 2007.

Saez suggests that this “may … help explain why the dramatic growth in top incomes during the Clinton administration did not generate much public outcry while there has been a great level of attention to top incomes in the press and in the public debate since 2005.”

So let me check that I have this right: given 100 people, of whom one is in the 1% and the other 99 are in the 99%, if these 100 people are given $1000 to distribute according to the “recovery” distribution, then Mr Onepercent gets $900, and the 99% each get $1.01 each?

That is about right.

See table 1 and the accompanying note in the Saez paper to which I have linked.

He is looking at the change in income over 2009 and 2010, which increased overall by 2.3%, but by 11.6% for the top 1% and 0.2% for the 99%. Also note that this includes all sources of market income, not just earnings but also capital gains. The suggestion is that a large part of these changes had to do with the recovery of the stock market, just as did the drop in the income share of the top 1% in the previous period (2007-2009). During those years average income fell by 17.4%, but by 36.3% for the top 1% and by 11.6% for the bottom 99% — the top 1% accounting for 49% of the loss.

One point of the paper is that the changes in 2007-2009 are entirely cyclical and should not have been taken by some as a change in the underlying trends. The more recent data for 2010 set this story straight.

Nope. Do the arithmetic again. If the top guy gets 93%, he walks away with $930 and the other 99 people get 70 cents each, on average.

So let’s do the numbers so the 99% each get $1: then Mr. Onepercent gets $1315, and the ratio is 1315:1.

That’s an awful lot of food stamps.

What implications would this have? Bastille?

Are you really going to look at a single year of data like this to arrive at a conclusion? That is simply nutty. What conclusion would you have arrived at in 2008 if you had used the same kind of statistic? Incomes for the top 1% fell while incomes for the other groups increased.

My understanding of this debate, and the significance of this most recent publication by Saez, is that the issue you raise is exactly the point. Some observers saw the 2008 numbers and inferred that this implied a change in the underlying trend. The updated numbers make clear what others argued: that it was a temporary shock related to the recession. The significance of the new numbers is not found by just looking at the one year change, but noting that this change implies that the underlying trend is still there.

Okay, but how much should the Top 1% have reaped compared to how much they actually got?

Clearly this is presented as an observation only, but in reality it carries deep emotive undercurrents of injustice and unfairness. I suspect that when many people see this they are moved to anger or at least frustration.

The only way to establish whether this observation has any moral or social justice implications, however, is to test it against a theory of how the distribution of gains should have been shared in 2011.

After all, what if some transcendental institutionalist theory showed that the Top 1% were in fact entitled to 99% of all the gains in 2010? If that’s the case, then we should cry out that the Top 1% aren’t getting enough of the gains!

This obviously applies to the broader debate over inequality, which is impossible to dissect in a few blog comments. But I just wanted to say that I worry when we present data which clearly packs an emotive punch, without articulating a more hollistic theory in whose context we should see the data.

I certainly agree with you, but getting the facts right is certainly a first step in having this sort of discussion. The real question would appear to be whether we want them to happen with an awareness of what is actually happening or in the absence of that understanding.

I agree wholeheartedly; having the facts in hand is essential and I would very much like to be one of the people that discovers the facts in the future.

But I wonder if having the facts first is actually the right way to put it. Maybe first we need a theory of what ought to be and then we proceed to measure what actually is (this is more or less the point I make in a post I just made on your latest blog entry).

I say this because I think it’s easy to discover a set of facts and then make those facts into an ideology. For example, I suspect that there are quite a few people that see the numbers on inequality and immediately respond with disgust. They say “inequality is too high” or “the rich are getting richer” or something like that. But compared to what? What benchmark informs these statements?

The facts are facts, but the RESPONSE to the facts, which ultimately will shape the next set of facts that we discover, depends on the context and the theory presented along with the facts.

I say this because we, as researchers, do have a responsibility to deliver more than just facts to the public (which ultimately shapes policy). Delivering facts without counterfactuals, delivering facts without null hypotheses, delivering a story of “what is” without arguing “what ought to be” leaves us open to the possibility of inspiring all the wrong reactions from the public.

And again- the reactions will shape the next set of facts we discover.

We can say: “the Top 1% has received 90% of the income gaines”. That implies something.

Or we can say: “the Top 1% has received 90% of the income gains, which is in line with what we would expect given the changes in the structure of the economy and the prevailing labor market conditions…” This also implies something, but surely different from the previous statement.

I don’t know. I haven’t thought that hard about this so I might be incoherent. But I hope my point makes at least some sense.

The 1% are obviously a smaller population than the 8.2% of Americans who are currently counted as unemployed. Those 8.2%, and the people who are so poor that they aren’t even counted any more, are regularly targeted by budget cuts, although most of them, if not all of them, have already lost a great deal of their income – and dignity. They can least afford the reductions and would benefit greatly from growth in their income, and because they can’t afford to save, any increases they see are spent in the local economy rather than being put in a bank. This increases the amount of money in circulation locally, which stimulates growth. Which, it is widely believed, is good for the economy. Allegedly.

The 1% are so rich that they could afford to give up their gains, and then some. They don’t need it, they don’t spend it. They wouldn’t miss it. Some of them even ask to be taxed more. With a little effort, the richest country in the history of the world should afford to bring its poorest citizens out of the misery of poverty.