There is a movement afoot, and there is an election in the offing. Always a great dance to watch, no matter what the issue.

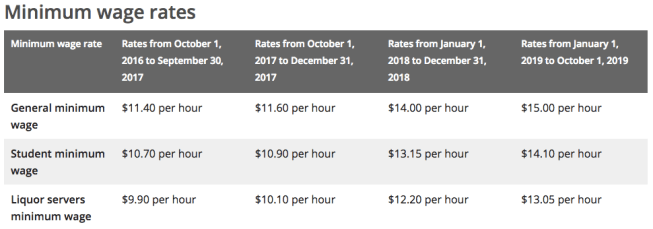

The latest show is taking place in Ontario, where “$15 & Fairness” is the rallying call for raising the minimum wage, and has found a willing partner in the province’s Premier who will go to the polls in the spring, but in the meantime has legislated significant increases in the minimum price for an hour of work. The same dance plays out in the United States, and in many cities and states a minimum wage of $15 per hour is becoming a reality.

The big question in Ontario is exactly that raised by The New York Times during the 2015 primaries when Bernie Sanders was battling Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination: “As the campaign for a $15 minimum wage has gained strength this year, even supporters of large minimum-wage increases have wondered how high the wage floor can rise before it reduces employment and hurts the economy.”

Something to think about, but how would you think about it if you were an economist? Here are four rules of the road that might come in handy regardless of which dance you might be watching next time.

1. Put things into perspective, get a sense of the magnitudes

The headline of a January 3rd article in Toronto’s largest circulation newspaper, The Star, is entirely accurate, and completely misleading.

Fortunately, the article summarizing an analytical study from Canada’s Central Bank is much more helpful because it puts the magnitudes involved into perspective. Well, almost. The meaning of this line in the article really rests upon your understanding of the word bleak: “The Bank of Canada report joins other reports in painting a bleak picture of the effect of wage increases.” Bleak … for whom? Workers or businesses?

Your first rule of the road when thinking like an economist is to get a sense of scale. Is 60,000 a big number or not?

It is not, and furthermore it has a lot of statistical fuzziness associated with it.

Statistics Canada reports that 18,648,000 Canadians held a paying job last December, reflecting a rise of 78,600 during the previous month. A change in employment of 60,000 “by 2019” amounts to something like 5,000 a month, and doesn’t seem so large in this context. This is much less than the rounding error Statistics Canada associates with its statistics, and even the Bank of Canada study admits that its estimate could reasonably be half the size, or twice as large. You don’t even have to read the opaque text to see that, just scan the one-paragraph summary.

Besides, this is a number for the country as a whole, examining scheduled increases in all the provinces, not a specific estimate of the Ontario impact.

Bottom line?

If raising the minimum wage has a negative impact on employment, it is not much at all. So if you are an employer, and particularly a small business in a very competitive industry in which you don’t have much room to raise prices, then yes, this might be described as bleak. But if you are a worker, chances are this will not cause you to lose your job, and your income will go up.

The Star headline could just as easily, indeed probably more accurately, have read: “Minimum wage increases put more money in the pockets of low wage Canadians.”

Now you have a sense of why there is so much heat on the dance floor. This is about how the pie is being sliced, and raising the minimum wage is going to put more money in the pockets of some workers, less in the bank accounts of some business owners.

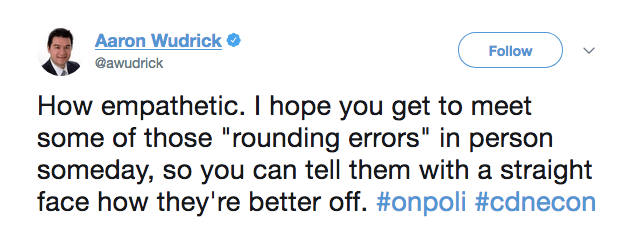

No wonder there’s a lot of fuss, and why some will love headlines that scream about the possibility of job loss, however minimal they appear to you—the economist with a sense of scale—and the other coldhearted number-crunchers at the Bank of Canada.

But your job is not done. After all, a careful look shows that the minimum wage changes are not trivial, and they have been implemented with urgency. The legislation implies a slightly more than 20 percent increase, whether in general or for students, on January 1st, and puts forward another 7 percent next year.

Also put this in context.

Statistics Canada reports that for the country as a whole the average wage is about $15 to $16 per hour for 15 to 24 year-olds, and between $28 and $29 dollars per hour for those older. So the job market for young people is heavily influenced by the minimum wage, and more generally the new minimum wage rates are approaching or higher than one-half of the overall average wage for adults.

A quick way to do a little research is to get into the habit of following trusted sources on Twitter. Lindsay Tedds and Trevor Tombe are two among many Canadian economists who do a great job, and are particularly timely on this issue. Their tweeter feeds offer some historical context, and show that the Ontario minimum wage has rarely been this high, and has never increased by so much, so quickly.

There is more to this story, and you need to keep thinking.

2. Labour markets are dynamic

Your second rule of the road is to draw on a wealth of knowledge about the astounding dynamics that characterize the job market.

When Statistics Canada says the number of employed increased by 78 odd thousand last month, what it means is that hundreds of thousands of jobs came to an end—either through layoffs or quits—and hundreds of thousands of jobs were started through new hires.

The monthly layoff rate is around 3 percent, the quit rate somewhere between 1 and 2 percent, and about another 1 percent of the employed move from one job to another. If there is something like 18.5 million employed people in recent months, then something like 550,000 will be laid off, and somewhere around 200,000 to 300,000 or more will quit their jobs. A good many others will be hired after looking or not even looking for a job, and others will move between jobs: hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people change places every month.

Last month, the net result of all this destruction, creation, and movement was a positive 78,600. It is in this sense that the economy “created” jobs. Flux, change, movement, are the metaphors you should be using to understand the job market.

And this perspective allows you to appreciate that there are consequences to higher minimum wages, even if the overall number of jobs doesn’t change much in the short run.

I’ve taken the information on layoff and quit rates from a nice research paper by my University of Ottawa colleague Pierre Brochu and his co-author David Green. You can read it, or a brief summary they also wrote. Here’s how the process works.

Businesses rarely lay workers off when the minimum wage goes up. Two things happen instead.

The immediate response in the face of higher wage costs is to adjust by slowing hiring rates, and let the natural attrition of workers gradually lower the rate at which employment costs grow. For the most part, we are talking about existing firms not growing as fast as they might.

At the same time we should appreciate not only that workers are less likely to quit, but that layoff rates actually fall as firms become more invested in their more loyal and productive employees. So in some sense a high minimum wage economy is different from a low minimum wage economy, even if on net the overall level of employment is roughly the same. There is longer job tenure and lower hiring, jobs are more stable, the jobs market is less dynamic.

Ironically, this adjustment process implies that you are less likely to lose your job, but if you don’t have one, you will spend a longer time looking, particularly if you are a teenager.

When we are in this dynamic frame of mind we can more clearly appreciate what all the fuss is about.

The change in the Ontario minimum wage may have been so large, and introduced too quickly, for this evolutionary adjustment process to work its magic. Quit rates fall immediately, but lower hiring doesn’t have time to have an impact, and wage costs go up without any increase in revenues.

In other words, in the short-term it is all a fight over a fixed pie.

Basically, you can think of higher minimum wages as giving workers greater bargaining power; think of them as a proxy for unionization, at least in the short-term. Eventually, and particularly if there is higher productivity from a more stable group of employees, or if there is robust growth around the corner, the fuss will die down.

When things settle down, higher minimum wages may contribute to changing the nature of the labour market: there are more stable jobs for less educated workers that are harder to get. This is the way Brochu and Green summarize their research:

the results for less educated workers imply that an increase in the minimum wage results in more stable jobs, but fewer of them. Thus, the policy debate should not just be about the employment rate effects of minimum wage increases but about the trade-off between good jobs with higher wages and more job stability versus easier access to jobs. And the debate is relevant for all of the low educated labour market, not just teenagers.

3. Time matters

The third rule of the road has been implicit in our entire discussion. Let’s put it on the table.

We have used words like “eventually,” “short run,” “long run,” and “when things settle down.” Time matters, and the economic effects in the short run can be very different in the long run when businesses have more time to adjust by changing their investments in their workers, and in the way they do business.

When they do hire workers, business will be more discerning, and be more inclined to give jobs to the most productive among potential candidates, who as a result are less likely to be laid off in the future. To make them more productive, and reduce the labour costs associated with producing their stuff, businesses will invest in them, and in new equipment.

The restaurants of the future? Well, they are going to polarize into, on the one hand, a high-end of quality, unique consumer experience, and refined service requiring a dedicated and savvy labour force, and, on the other hand, a low-end of standardized products and automated delivery with little human interaction.

My favourite example of the later is the Cupcake ATM on Lexington avenue on the upper east side of Manhattan.

But heck, you don’t have to move to New York to see this, just walk into your closest MacDonald’s, which has changed a good deal since I worked in one as a teenager decades ago, even if the menu hasn’t.

Besides, I’ve never been a fan of the obvious inefficiencies of lining up at a Tim Horton’s drive thru anyways. It can’t be so far down the road, if the corporation can prove to be enterprising enough, before this is replaced by some sort of fancy spigot, that will be quicker and leave us pleased with our double-doubles, much in the way the cupcake ATM leaves its patrons giggling with delight.

In the long run, businesses have more scope to adopt these changes and economize on low-paid, low-skilled workers. Those that don’t adapt may disappear, and others will take their place in a new form.

4. Policy is endogenous

My own view is that this process has been going on for some time, and is driven as much, even more, by the very sharp falls in the cost of capital equipment than in the rising cost of labour. It is relative prices that matter, and the comparative cost of capital—thanks in part to computerization—has fallen tremendously, minimum wage increases or not.

My point is that increases in minimum wage rates are as much a result as they are a cause of labour-saving investments.

Policy is endogenous. Trust me, I’d be failing you if I didn’t burden you with that word. “Endogenous.” Just don’t go to Wikipedia for the definition. An absolutely essential rule of the road for economists navigating public policy discussion is to recognize that things interact and influence each other. The changing nature of work is as much an influence on the policy process, as the policy process is on the nature of work.

So what is all this really about? It is easy to portray this, as I admit I partially have in the introduction, as an opportunistic politician looking for a wedge issue in advance of an election. But there is more to it than that. The politician is responding to the growing inequality in the job market that makes it harder for low educated workers to climb the ladder to the middle class, to the growing insecurity of many others, and to the more challenging job prospects of the young.

Minimum wage increases weren’t dropped onto the stage out of the blue, they are a response to a deeper need or anxiety among some significant fraction of the population. That is why they might be perceived to have political traction.

The question this leaves you with, and which has been missed in much of the public discussion, is whether higher minimum wages, by themselves or in combination with other policies, are the best way to develop a more inclusive labour market with less inequality in the bottom half of the income distribution. If all of this is about income distribution, then we should debate that directly.

That debate will surely flare up in the coming months, and you will need your rules of the road as the provincial government learns lessons from its basic income pilot and moves to reform income assistance, as the federal government proposes changes to the Working Income Tax Benefit in its next budget, and as the country begins to debate how to implement a Poverty Reduction Strategy.

Professor Corak, Excellent overview of a timely topic. The issue for me is adjustment . In particular How long will it take businesses to adjust to a higher wage bill? And how will they adjust? Businesses will always substitute cheaper capital for more expensive labor. Hence they will gradually reduce the number of workers on the payroll if workers can be replaced by machines. For example , Self checkouts at supermarkets may become the norm. But can businesses eventually pass on labor costs to customers so they may eventually preserve their share of the pie aka rate of return on capital employed. Many businesses have done so in the past. Recall Henry Ford with his 5$ daily minimum wage , still passed on to customers in their SUV prices. Accordingly , I Expect that the Tim Mug of coffee will cost a bit more eventually. And will workers still benefit ? Of course they will, but only if they save a bit of that wage increase.

You missed the general equilibrium effects. A higher minimum wage means more consumer spending by those workers.

And you missed the price effect. A higher minimum wage can move the price point for monopolistic and monopoly sellers. This might negatively affect seniors on CPP.

And you missed another effect. If this increases job security for the already hired, they also spend more.

Thanks for this, very helpful.

In fact, the Bank of Canada study looks at some of these other consequences in a general equilibrium framework, finding that consumer spending is not much impacted, nor is there a big impact on inflation.

You also raise a good point about market structure, which also applies to labour markets. When labour markets are dominated, as some local labour markets and markets for some occupations, by a single buyer — that is “monopsony” — then economic theory implies that a higher minimum wage may lead to higher employment. This is the model that David Card and Alan Krueger end up using to explain their findings of little impacts of minimum wage increases in their case study, fast food restaurants in New Jersey. Their book is now a classic in the minimum wage literature. https://press.princeton.edu/titles/10738.html .

I dunno if the BoC GE model is going to pick up things like monopolistic/oligopolistic sellers’ price strategizing: if their consumption good is priced according to a perfect competition assumption then they’re going to have a price-setting mechanism that’s not empirically valid.

BTW, as far as the McDonalds kiosks are concerned, I see them as a technology to increase throughput and thus increase marginal product of labour (and decrease fixed costs per unit), the former of which in the classical model should result in *higher* wages. After all, each McD outlet has a maximum throughput determined by its “technology”: attempt to exceed that throughput only means longer lines, and eventually loss of customers. So the kiosks shouldn’t be represented as a loss to labour.

That there’s two big problems I have with econ models: one, there never seems to be an awareness of hard limits, in this case the hard limit to throughput given a technology level; and two, there seems to be little awareness of how companies actually make decisions and set prices.

For context wouldn’t it be better to examine the number of workers at or below $15/hour?

Exactly!

Very good presentation of the issues as conventionally viewed.

I have a rather different starting point, however. I favor a living wage as an efficiency policy. Any adult earning less than a living wage must depend, at least partly, on some other source of support – government assistance programs, family members, friends. Essentially, these alternate sources of support allow the worker to sell his/her labor at less than cost. The employer receives a subsidy in the form of below-cost labor. The employer’s customers do not pay the true, full cost of provisioning the product or service; hence more of the good/service is produced than would be in a properly functioning market, and fewer goods and services from above-minimum-wage employers get produced.

Of course transitioning to a living-wage economy would have to be paced so as to manage disruptions, and certain exceptions for youths and other dependents, internships, and the like.