It is sometimes said that think tanks are good for democracy; indeed the more of them, the better. If there are more ideas in the public arena battling it out for your approval, then it’s more likely that the best idea will win, and that we will all have better public policies. But intuitively many of us have trouble believing this, have trouble knowing who is being truthful, and don’t know who to trust.

This battle of ideas, studies, and statistics has the potential to make many of us cynical about the whole process, and less trusting of all research and numbers. If a knowledgeable journalist like the Canadian Kady O’Malley expresses a certain exasperation that think-tank studies always back up “the think-tank’s existing position,” what hope is there for the rest of us? A flourishing of think tanks just let’s politicians off the hook, always allowing them to pluck an idea that suits their purposes, and making it easier to justify what they wanted to do anyways.

Maybe we shouldn’t be so surprised that think tanks produce studies confirming their (sometimes hidden) biases. After all this is something we all do. We need to arm ourselves with this self-awareness. If we do, then we can also be more aware of the things in a think tank’s make-up that can help in judging its credibility, and also how public policy discussion should be structured to help promote a sincere exchange of facts and ideas.

1. Begin with the idea that “think” tanks don’t think

Well that’s overstating it, but what I mean is they are not guided, appearances to the contrary, by reason alone. But then again, none of us are. Our intuitions come first, and the reasoning side of our minds serve to justify those intuitions.

Many academic economists are very quick to dismiss think tank research because they see these studies as falling on the wrong side of the line between examining the economy as it is, and advocating for an economy as it should be: a distinction that Milton Friedman called “positive” versus “normative” economics. In a famous essay published in 1953 the late University of Chicago economist wrote:

Positive economics is in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments. … it deals with what is, not with what ought to be. Its task is to provide a system of generalizations that can be used to make correct predictions about the consequences of any change in circumstances. Its performance is to be judged by the precision, scope, and conformity with experience of the predictions it yields. In short, positive economics is, or can be, an objective science. [ Milton Friedman (1953). “The Methodology of Positive Economics,” in Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, page 4. ]

This is an important touchstone for serious social scientists, and dressing up, inadvertently or not, normative research as positive science is crossing a line from professional to political. They would consider this a serious loss of credibility.

But we all know that this line is sometimes hard to draw, and in fact Friedman went on to write:

Of course, the fact that economics deals with the interrelations of human beings, and that the investigator is himself part of the subject matter being investigated in a more intimate sense than in the physical sciences, raises special difficulties in achieving objectivity … [ Friedman (1953, page 4) ]

The whole field of moral psychology has developed since he wrote this, and makes clear that our intuitions are automatic and instantaneous. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt, who teaches at the New York University’s Stern School of Business, offers a masterful discussion of the challenges of engaging in what he calls “exploratory” thinking—of searching scientifically for the truth—in the face of a strong human tendency of falling into “confirmatory” thinking—of seeking evidence to support underlying intuitions.

His first rule of thumb is “Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.” We are hardwired to be that way, and Haidt’s book offers an explanation of the evolutionary advantage our ancestors developed by evolving so that reason serves intuition, and that now leads people to “bind themselves to political teams that share moral narratives. Once they accept a particular narrative, they become blind to alternative moral worlds.” [ Haidt (2012, page xvi) ]

As a starting point, remember, think tanks don’t think.

2. Be aware of the underlying intuition

So while we might all strive to attain Friedman’s ideal of objective, scientific inquiry, when it comes to think tanks it’s probably best to, in Haidt’s words, “Keep your eye on the intuitions, and don’t take … arguments at face value.”

But this is a big challenge, all think tanks seem to tell us they are “non-partisan.”

If we understand this to mean “objective,” or “scientific” (as opposed to not being formally affiliated with a political party), we should appreciate they may well be sincere in telling us that. But that should not be enough.

Consider this exchange between the noted journalist Steven Paiken, who appears to be somewhat surprised by a representative of what, he suggests, many recognize as the most right-wing think tank in Canada. The discussion with Mr. Jason Clemens of the Fraser Institute, part of a panel discussion on the role of think tanks in public policy broadcast on a popular current affairs program, begins after the other two panelists have placed their organizations on the political spectrum.

Then Mr. Paiken turns to Mr. Clemens (just after 8 minutes into the program):

“Jason I think everybody would put a label on your organization. It’s unabashedly, they would say, right-wing. Do you subscribe to that?”

“… Our approach is we are an economic think tank.”

“So where are you on the political spectrum?”

“We don’t worry about the political spectrum. … “

“We worry about picking issues that are important … and then using an accepted, quantitative approach to asking and answering questions. In fact, our motto here … is ‘if it matters, measure it.’ And so if you look at most of our research, it’s measurement approach because, as we learn as researchers, you can’t argue about 2 plus 2 equaling 4. … Our approach is to quantify things.”

The exchange continues all the way to 15:22, and there is nothing Mr. Paiken can say to get him to drop, even just a bit, the veil of objectivity with which he has cloaked his organization.

In some sense this is natural, we all do it. Haidt says “We are indeed selfish hypocrites so skilled on putting on a show of virtue that we fool even ourselves.” [Haidt (2012, page xv) ] We have no basis to question Mr. Clemens sincerity, it just means that we need an independent guidepost to the underlying intuitions because we can’t expect those to be explicit.

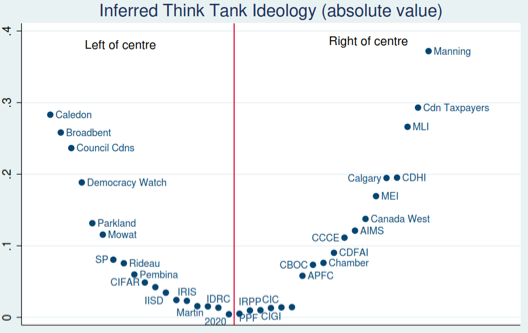

Stephen Tapp makes our challenge a bit easier by offering an excellent application of the “if it matters, measure it” principle to uncover the underlying intuitions of Canadian think tanks. His blog post called “What can a little birdie (Twitter) tell us about think tank ideology?” uses information on the followers of a long list of Canadian think tanks to rank them across the political spectrum.

The best way to explain his method is through example. If I were a think tank, Mr. Tapp would have gone to my Twitter account and noted that (as of November 22nd, 2014) I have 2,634 followers. Of these 153, or 5.8%, also follow the Fraser Institute—which Mr. Tapp takes as his touchstone for “right wing”—and at the same time do not follow the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternative, his touchstone for “left wing.” Similarly 327, or 12.4%, follow the Centre but not the Institute.

My score on the political spectrum is the difference between these percentages, -6.6 (or -0.066 if we were to express this a fraction of 1 rather than 100), the negative indicating that my followers are more likely to be following the paragon of left wing think tanks in the country than that of the right. In this sense I would be a “left wing” think tank, a bit left of centre.

He does this for all the think tanks in Canada, and displays the results as follows. (You can visit his blog post to get the names of all the organizations if that interests you.)

A similar type of ranking for American think tanks is offered in the first column of the first table in this 2005 paper by Tim Groseclose and Jeffrey Milyo, published in the Quaterly Journal of Economics. It is based upon the number of times members of Congress cite the think tank, and ascribes the political leanings of the members—which can be measured pretty accurately—to the think tank.

You should have maps like this in your mind, but obviously they can’t offer the whole story, as Mr. Tapp, for example, is quick to acknowledge.

We should also appreciate that think tanks may be more likely to engage in exploratory thinking rather than confirmatory thinking depending upon how they are organized. We should also look at their organizational structure.

Here’s a paragraph from Jon Haidt’s book worth quoting:

We should not expect individuals to produce good, open-minded, truth-seeking reasoning, particularly when self-interest or reputational concerns are in play. But if you put individuals together in the right way, such that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, and all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning …. This is why it’s so important to have intellectual and ideological diversity within any group or institution whose goal is to find the truth (such as an intelligence agency or a community of scientist) or to produce good public policy (such as a legislature or advisory board). [ Haidt (2012, page 90) ]

If you see an organization tightly beholden to funders, so that “self-interest” is at play, or an organization dominated by like-minded individuals without diversity of ideological perspectives, then it will be harder for this organization to play the game on the “positive” side of Milton Friedman’s line.

3. Place more credence on conversation than on debate

It’s not just organizational structure that matters, but also how the interaction between think thanks is organized. Haidt points out that we are more likely to change some one’s mind if the interaction is “civil.” He suggests that “[i]ntuitions can be shaped by reasoning especially when reasons are embedded in a friendly conversation.” [page 71.]

The metaphor of public policy discussion as taking place in some sort of arena with the gladiators fighting it out until only one is left standing is not helpful. You should wonder about the value of debate, since this type of forum puts reputations on the line, and hardens positions. Put more credence on interactions that can be characterized as conversation.

Here are two examples that touch me in a personal way, the policy discussion about the relationship between inequality and economic opportunity.

The first is conducted as a debate, one that took place in New York City on October 22nd, 2014 and organized by Intelligence Squared U.S. If you’ve never watched any of these, you should. The debaters are always articulate, the moderator is excellent, and the topics are provocative. But as you can appreciate the debaters must feel that their reputations are on the line, after all they are under pressure to change the opinions of the audience members, who are polled both before and after the debate. The side swaying opinion the most is declared the winner. Galidators in the arena, indeed!

In this case the motion is “Income inequality impairs the American dream of upward mobility“. For the motion are Elise Gould and Nick Hanauer; against Edward Conrad and Scott Winship. You don’t have to watch much of the debate or read much of the transcript (by clicking on the above link), to realize that there is nothing either side can say to the other that will lead them to change their mind.

This is a format, I might suggest, that in Haidt’s view will harden the participants’ reasoning in way that reinforces their underlying intuitions. It is terribly entertaining, and informative, but it puts a premium on performance. As audience members, we may well wonder about the veracity of the facts being thrown back and forth, and in the very least that some subtly in interpretation could well be lost.

Here’s one example. It deals with the descriptive relationship across countries between inequality and the degree to which individual adult income is related to parental income during childhood, the so-called Great Gatsby Curve about which I, among others, have written.

Scott Winship of the Manhattan Institute has been a persistent critic of this relationship. I bring this up, in part, because I also want to go on the record and note that when he says my “most recent paper highlights serious problems [with the Great Gatsby Curve and my] previous research,” it should be clear that this is Mr. Winship’s interpretation of my research, and not my understanding of my own research.

Grateful as I am to have a reader, I don’t feel my more recent work involving a three country comparison contradicts previous papers I have written. I certainly don’t have any reason to question Mr. Winship’s sincerity, he must believe what he says. But he’s never checked with me before he has written or spoken on the subject, we’ve never had a conversation about the issue, not even on one occasion when we sat across the very same dinner table together.

Here’s an excerpt from the transcript.

The real the point is that it must be hard for the audience to make a judgment on what’s right, what’s wrong, what’s more subtle and could be right, and where there’s scope for agreement. This is one instance in which you can just see “reason” going to battle for “intuition” in this kind of forum (and now I have to admit I’m also speaking for myself!).

Contrast this format with a conversation on pretty well exactly the same subject between two individuals who, most informed people would reasonably suggest, lie on opposite ends of the political spectrum, Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute and Timothy Smeeding of the University of Wisconsin. At one point the moderator expresses surprise at the extent to which these two guys agree, even noting that they are wearing the same kind of shirt!

After watching this I’m thinking that it would be interesting to have dinner with Charles Murray.

Conversions require leadership, goodwill, and civility. So look not just at who is speaking, but the structure in which they are placed. Conversations have more credence than debates.

4. Full disclosure

I think think tanks are valuable, and I have engaged with a number of them. Their great strength is that they offer academics what they so often lack, both a communication strategy for research that deserves a wider audience as well as a fountain of policy relevant ideas that deserve more research.

Organizations, like individuals, are more likely to be open-minded and engage in exploratory thinking when they are accountable to a broad audience, whose views are not fully known ahead of time, and who are well-informed. So when you think about think tanks, think about who they are speaking to, and recognize that quite possibly we get, in the end, the think tanks we deserve.

[ This post is published in an abbreviated form under the same title in the January/February 2015 issue of Policy Options by the Institute for Research on Public Policy. ]

I remember when I was an economic adviser at the Assemblée NAtionale in QUébec City. Me and my colleague always disagreed. Young and somewhat naive, I asked my boss why he had two advisers at loggerheads. He loked at me, smiling:”So that whatever I decide, I can say that my adviser told me it was the best decision.”

You might be interested in sociologist Tom Medvetz’s work on think tanks, especially his book Think Tanks in America: http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo13181062.html

thank you, this is helpful

Reblogged this on Multicultural Meanderings and commented:

Interesting observations on think tanks.

I am far too cynical to believe anyone presenting/speaking to media or acting as media is not biased. Perhaps these non-profits could disclose their donors and funding to better colour their flag.

Too many studies are thin on substance and too broad on statements or conclusions. It would be best if Think Tanks/academics would disclose their assumptions upfront in their papers rather than burying them and extolling their conclusions. However, that wouldn’t serve the overall purpose of these studies, which is to solidify their political ambitions into policy. They do this with strawman arguments, obfuscated or contrived analysis and predrawn conclusions. I see it as no different than reading actuarial reports of financial statements if assumptions are buried or obfuscated then the papers are meaningless if not dangerously mis-informative.

Think Tanks try to present or translate empirical data through a lens that is either framed by assumptions or political views, but without disclosure the conclusions are just bald statements. Reputation means a lot, fir example I question any study presented by a Goldman Sachs analyst because in my view their complicity in market manipulation and self serving prestations. They could make all market recommendations they want, even correct ones, I won’t listen. Likewise I question the integrity of papers and studies by anyone given enough press because of the tabloid style presentation of the press and the opaqueness of the underlying assumptions in those studies.

I questioned the earlier statements by the CCPA on the tax incentives with limited income splitting, and asked for their data (which would have been interesting to have that familial tax data). I never got a reply or access to the data. Regardless the criticisms were limited if not deflated by the monetary limits imposed on the measure, and it really had less a political/media impact. Same when CD Howe criticized the PSSA (Federal pension) high on grand assumptions light on details. Think tanks are blowhards on a soapbox, those that paid to get off the comment section of news papers to tailor data to ideas.

This is a really valuable contribution to an important debate, thank you so much. Have you thought about reposting it on the OnThinkTanks blog?

Transparify, the organization I work for, rates how transparent think tanks are about who funds them. During our last rating round 2013-2014, we found that a majority of them were opaque about where they get their money from:

http://bit.ly/1tecPkY

We’re about to start re-rating them all this December, and expect more positive results. We believe that financial transparency is the best starting point for signalling research integrity – regardless of who your funders are.

For a quick overview of interesting debates about think tank integrity, see the annotated bibliographies at

http://www.transparify.org/publications-main/

thank you

Background of conversations and ideas are definitely a core component we’ve slowly forgot to pay attention to in our fast communications world. Biases are part of the discussion, they actually provide its dynamic. We should relearn to read between the lines and take a step back from the instantaneous thinking mode, try to get the big picture, from our own standpoint, acknowledging we’re biased as well. May be we could turn this bias into a value. May be this is what think tanks try to do? I’ve written a post on how our biases turn out to be our personal language: http://weareinnovation.org/2014/11/07/whats-your-personal-language/

I may refer to your post on a later issue if that’s OK.

Thanks a lot for this thoughtful piece.

“Academic economists” are just as biased as think tanks. Their “findings” are just as predictable if you are familiar with their position on the left-right economic spectrum. On the right side they have the same proclivity to hide their position on the spectrum, especially in Canada.

First, one needs to define the left-right spectrum (which doesn’t change as the pendulum swings.) Furthest left is communism, which means full government control of the economy. Furthest right is libetarianism, which means no government involvement in the economy. In the center is the mixed-market system created by John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression.

In the post-war era (1945-1980), political leaders were Keynesian: from Eisenhower to Kennedy to Nixon to Carter; from Diefenbaker to Pearson to Trudeau.

The present era has been dominated by the New Classical economics and free-market reforms of Milton Friedman. One could go so far as to say, we’re all Friedmanites now (despite the ill effects these policies have had on the Western economy, including economic collapse.)

Academic economists obviously cover the entire gamut. Any strength in numbers of any particular brand does not imply credibility.

Centrist and social democrats favor Keynesian economics. Small-government low-tax conservatives favor New Classical ideology. New Keynesians are right-of-center embracing a synthesis of Keynesian and New Classical thought. Austrians are right of New Classical economists. Etc.

So academic economists can brag they have a consensus on, say, monetary policy in our present slump. Certainly Keynesians, New Keynesians and New Classicals will all agree loose money will not produce high inflation. But all have different interpretations.

Keynesians favor fiscal stimulus saying trickle-down helicopter money is the equivalent of pushing a string. New Keynesians will favor fiscal stimulus, but only in a liquidity trap. New Classicals will say that any fiscal stimulus will be ineffective (Krugman explains their arguments in “The Unwisdom of Crowding Out”)

Keynesians also favor a loser (dual mandate) inflation target, around 4%. As Stiglitz says, inflation fighting can cause inequality and there’s a conflict of interest between bondholders and workers.

In short, economics is the agenda-driven science. Which means it isn’t. Everyone has an economic bias. It reflects the kind of society a person thinks we should have. Left-leaning is more egalitarian, lower inequality. Right-leaning is more hierarchical believing inequality is justified and merit based.

The only way economics can be made a science is if we sort out these biases. That way we will know which bias gets the best results (e.g., GDP and productivity growth, economic stability and sustainability, etc.) and which bias best reflects the will of the people.