If there is a thread running through the books I read this summer I suppose it is inequality: its causes and consequences; the real life and not so real life—but no less true—experiences of living these causes and experiencing the consequences; and what can—or for that matter can’t—be done about it.

Inequality in earnings and incomes has been a very hot topic in labour economics for the last two decades, but the relevance of this research and its use in public policy discussion has now become strikingly clear.

My last academic year was dominated by the rise of inequality on the public and public policy radar screen, and I have been so tied up in these discussions that I was carried, as if on a train leaving the station, right along throughout the entire summer.

I re-read a speech President Obama made on the topic. Last December he spoke about a type of inequality that “hurts us all”, and made a link between equality of outcomes and equality of opportunities.

The Chairman of his Council of Economic Advisors—Alan Krueger—gave this relationship more precision in a speech presented in January, and in the Economic Report of the President released a month later. He brought together information on a number of countries, and noted that those with more inequality are also countries in which the adult outcomes of children are more closely tied to their family background. In unequal countries there is more of a tendency for the rich to see their children grow up to be rich, and for the poor to have their children become the next generation of poor.

Krueger relied upon data I had put together based upon research from the community of labour economists to which I belong. Most notably, John Ermish, Markus Jantti, and Timothy Smeeding edited a book on the topic called From Parents to Children, which was at the top of my reading list.

The book is a collection of research papers examining why inequality and opportunity are linked. But good labour economics is not just about number crunching informed by economic theory and public policy concern, it is also about communicating the results in an appropriate way. Krueger’s labeling of the relationship between inequality and opportunity as “The Great Gatsby Curve” turned out to be a great communication device.

So when my daughter passed me her copy of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel, The Great Gatsby, first published in 1925, I could not turn away from the opportunity. You can hear an entertaining discussion of the significance of the novel, in literature and in economics, in this interview I had with CBC radio.

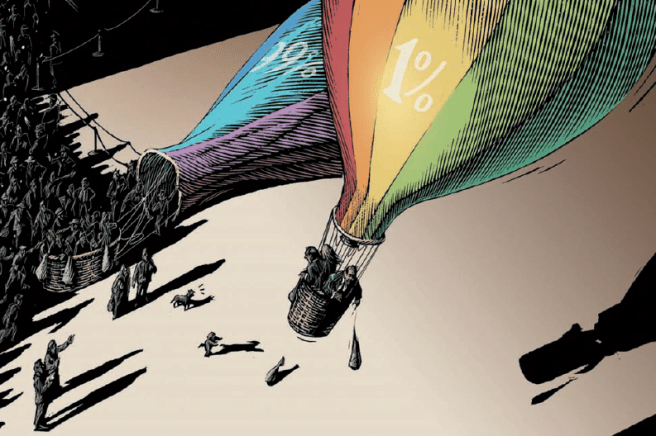

What really kicked off the popular interest in inequality last year was, of course, the Occupy Wall Street movement, which had its facts right: there really is an astounding distance between the top 1% and the 99%, something labour economists have been at pains to document during the last decade or so.

The other books I read addressed this theme.

These ranged from the very accessible and clearly written book by the journalist Timothy Noah—The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It—to the somewhat more challenging and hard-hitting book by the noted economist Joseph Stiglitz—The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers our Future—to the book that will likely become the policy wonk’s manual of choice, Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising, which is published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

I learned a good deal from Divided We Stand, several chapters of which were researched and written by a co-author and former colleague of mine, Wen-Hao Chen. It has the most nuanced and comprehensive discussion of what to do about inequality.

But none of these books directly relate inequality to opportunity, or talk about policy through the lens of the Great Gatsby Curve.

There is a real need for this kind of careful thinking, but I found public policy developments in the United Kingdom to be helpful in understanding appropriate policy options, and how the debate may play out in other countries. Nick Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister, owns this file, and his office released an update to the coalition government’s social mobility strategy that illustrates possible policy directions.

I gave a number of presentations to policy makers and politicians in the UK, Canada, and the United States during the spring and summer, including to a committee of the Canadian Senate and another to the US Senate Committee on Finance. There is certainly a hunger for good policy advice, and it is generally agreed that education and schools are central in determining how inequality and opportunity interact.

Finnish Lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? by Pasi Sahlberg is a provocative and informative look at how one country, Finland, transformed its education system from just average to something exceptional that promotes both equality and achievement.

All of these publications give me the impression that we understand a good deal about inequality, its causes and its consequences, and that there are important implications of this knowledge for the conduct of public policy. But policy is not made just on the basis of knowledge and evidence. With respect to the Canadian case, there are many experts on how public policy is actually made in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa, where I teach.

Many of my colleagues—Robert Asselin, Richard French, and David Zussman to mention only three—have direct experience in making government policy. But I have to admit that in spite of all this experience in the corridors around me I enjoyed and learned a good deal by reading a book called The Way it Works: Inside Ottawa by Eddie Goldenberg, an adviser to a former Canadian Prime Minister. The book is a bit dated, but it is honest, heartfelt, and an easy read … besides I stumbled upon a copy of the hardcover edition at my local goodwill store for only $3.00 !

On the role of politics in making public policy, I also read Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Power, a collaboration between the famed MIT labour economist Daron Acemoglu and the political scientist James Robinson. This is a big-think book that explores the reasons for inequality between countries. Small differences in public policies, reflected in the institutions that govern the nature of politics and economics, can make huge differences over time as societies evolve in response to outside events.

I am of the view that the relationship between inequality and opportunity is multi-faceted. Yes, as President Obama seems to suggest, labour markets and the inequalities embedded in getting good paying jobs matter; yes, education and other government policies matter; yes, the political process matters in determining how policies are designed, and for whom they are of relatively more advantage; but so do things that go beyond markets and governments.

How families work, how they give their children a reasonable start in life, and how they help them navigate all the challenging transitions they must make in becoming successful and self-sufficient adults is central to understanding the relationship between inequality and opportunity. And it is not entirely clear what public policy can—or for that matter should—do about the advantages and disadvantages we get from our parents.

The book that touched me most, that made clear how all these forces—labour markets, public policies, and families—come together to determine life chances, was Shania Twain‘s autobiography: From This Moment On.

Ms. Twain, the country/pop music superstar, went from the very lowest rung on the ladder to the very highest.

In this book she reflects, in a constructive way, on both the pluses and minuses of what can only charitably be described as a challenging family background, indifferent public policies, and rapidly changing economic opportunities, to tell a story that is the best possible antidote to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s pessimistic view of the American Dream.

She is a Jay Gatsby for our time. Like him she sought security and love, like him suffered tragedy and achieved financial success, and like him lost love. Whereas F. Scott Fitzgerald leaves us with a sense that the game is rigged, and that the 99% are better off not playing, Ms. Twain suggests otherwise, sending a message of hope and stressing the importance of strong will and self-determination, while at the same time throwing in a few scoops of practical advice.

Thanks for the reading tips. Regarding the issue, however, I must say I have enjoyed the work of both Karl Ove Moene (i.e. Likhet under press) and criminologist Niels Christie (i.e. Hvor tett et samfunn). But I am not sure how much of their work is available in English.

Branko Milanovic is good too, and of course the Spirit Level…

Thanks for the suggestions. Are you able to post for us the links to the books you have in mind?

A little evolutionary theory over economics perhaps?

Be sure to read the legendary Edward O. Wilson’s “The Social Conquest of Earth”. Not simply because in the field of evolutionary biology, Wilson’s promotion of group selection over kin selection as a critical evolutionary pathway is generating massive controversy. Nor the fact that Wilson has over-turned much of his own thinking from the last 40 years.

I think most of us recognize how much biological science has influenced the big ideas and popular images shaping our political and economic culture. Moreover, that these ideas and images promote the idea that human progress is welded to the individual and competition. Using evolutionary biology to “legitimize” inequalities in power and authority.

While I personally would have like to have edited the book in places, the value is what it represents. In the world of evolutionary biology and anthropology, more and more researchers are calling into question the emphasis on competition and individual as the traits of humanity’s achievements and are presenting rigorous evidence that cooperation and group are the truly critical factors in our social development and “progress”. “The Social Conquest of Earth” presents a deep scientific argument from the ruling king of evolutionary biology. The implications of social inequality from this evolutionary perspective are obvious…that fairness is not simply a moral good, it is an essential evolutionary factor in sustainable societal success.

P.S. Also worth a quick fun read is “The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons For A Kinder Society” by Frans De Waal from a couple of years ago. Some amusing empirical examples of how deeply rooted “inequity aversion” is within us, indeed, an innate characteristic of human nature? Worth a quick peek on youtube: Capuchin monkeys reject unequal pay http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8mynrRd7Ak

Thanks for this Ron. The video of the monkeys is amazing! I’m not certain about the joke at the end, that this explains the Occupy Wall Street movement: after all, the monkey getting the cucumber didn’t see the value of his cage collapse. 🙂

Miles, a very interesting set of readings. Re the role of families….once it is determined that families do play a critical role in reducing income inequality, it appears that a clear policy role exists for the relevant agencies of the state. Where the state provides income support to poor families ,it may be necessary to link this financial support to mandatory education of parents with respect to child rearing. Parents who have had little success in school themselves, may need to be taught how to assist in the home so that their children are not disadvantaged in the schools. Many parents of school age children may not realize how critical home support is and may simply not know how to create an ideal home environment for school success.

Thank you Dhanayshar. In fact, this is one of the policy directions that the UK government is currently pursuing, but in a way that has taken the emphasis off income support. While it may be important to develop parenting skills, it may also be important to understand how families interact with the labour market: the income in the household, the time stress the household faces are also important considerations, as well as the quality of alternative care arrangements. I am not certain what the optimal mix of support would be across these dimensions.

What do you think about Jeffrey Sach’s The Price of Civilization, or Paul Krugman’s End This Depression Now?

Also, what do you think of Bill Moyers “Moyers and Company”?

And lastly Dissent magazine?

Can we in Canada learn much from the U.S. organizations that focus on income inequality?

Jim … I am afraid that I have not read any of the books you suggest, nor the magazine! Maybe I should!! Please feel free to share the major messages if you think they are of value.

I do, however, think that there is a good deal to learn from US sources for Canadians and for those in other countries. Sometimes developments in the US directly influence us, and sometimes they foreshadow trends that will also impact us. An important example is the concentration of earnings in the top 1%, something that has its root causes in the US economy, but also spills over to impact over countries.

That said, there is also a tendency to not recognize that institutions and underlying forces are different, and play out differently … that things are very different in some respects in Canada. That is the value of comparative research. I hope this helps. Any thoughts you would like to add?

Miles.

Happy to Miles, upon return from Montreal and Ottawa this week. All are progressive in approach. Dissent very labour movement oriented. Reading Chris Hedges right now, Death of the Liberal Class.

Here is a New York Review of Books review link on Stiglitz’s and Krugman’s books. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/sep/27/what-krugman-stiglitz-can-tell-us/

Paul Krugman’s ‘End This Depression Now’.Paul Krugman summed up his book in a podcast available from The Commonwealth Club of California. He says the nature of the economic problem is not enough spending. The US was borrowing too much, there was too much leverage by the banks, there was reduced banking regulations. Somebody has to start spending. That being the government. Have the federal government provide aid to the state and local governments. Get hiring back more teachers , boost medicaid, infrastructure spending for example. Secondly, we need housing debt relief, thirdly student debt relief. We just spend more the recession would be over “faster than you can imagine”. We would be back to full employment within 2 years. In response to criticisms like ‘where will the money come from’, his reply is ‘markets are willing to lend to the US government at very low rates. There is cash waiting to be invested. So money is out there. This is not the time to slow spending’.

His presentation to the Club was quite humorous also.

I wonder if the same logic, if you agree with him, should apply to Canada. Instead of Harper slashing jobs in government, perhaps he should be doing the opposite.