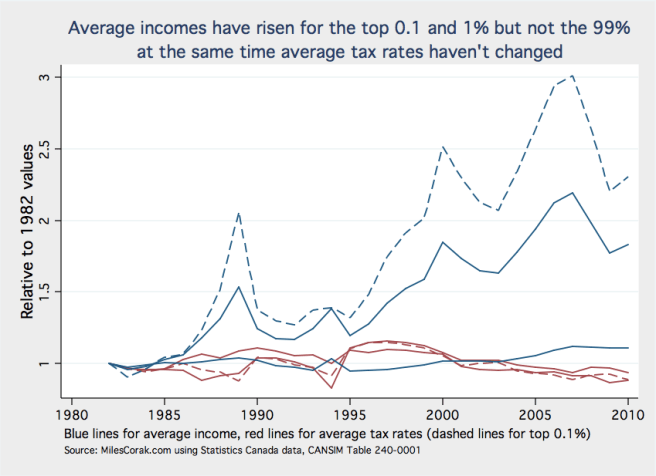

Everything you need to know about why the rich don’t want to talk about inequality, and why the 99% do, is right here in this chart.

The average income of those in the top 1% in Canada has about doubled since 1982, and for the top 0.1% it has increased by about two and a half to three-fold. But over this period the fraction of their income paid in taxes, their average tax rate, has remained about the same, and even a little lower.

During the early to mid 1980s the average income of the 99% was about $33,500 (measured in 2010 dollars), and by 2010 had risen to $37,200, amounting to about a 10% increase or a bit more.

Members of the top 1% were making about $260,000 to about $270,00 on average, but this ballooned, reaching a peak of $585,000 in 2007, and even after falling to $488,600 in 2010 was 1.8 times higher than in 1982. The changes for the top one-tenth of one percent are even more dramatic: their average income started at $777,940 and by 2007 had tripled to reach $2,344,210.

As a result top earners contribute a higher share of all the taxes paid by Canadians, and this has risen: the top 1% contributed about 13% of all taxes paid to federal, provincial and territorial governments during the 1980s, and 20 to 23% during the 2000s.

But in spite of these changes the average tax rate of all three of these groups, total taxes paid divided by total income, was pretty well the same over these almost three decades. In the early to mid 1980s top earners were paying about 30% of their income in taxes, three decades later about 30% or even a bit less.

Does the fact that the top 1% who make about 10% of all income but contribute 20% of taxes imply, in the words of an editorial in a major Canadian newspaper, that “They are a net benefit to Canada. Occupy that.” ?

Or does the fact there has been no change in the fraction of their income going to taxes, even though incomes have doubled and even tripled, indicate just the opposite: that they should be paying more?

Alfred Marshall in his Principles of Economics, the most used economics textbook from the 1890s to the 1920s, not just in Cambridge England where he taught, but in the whole English-speaking world, wrote that:

A rich man in doubt whether to spend a shilling on a single cigar, is weighing against one another smaller pleasures than a poor man, who is doubting whether to spend a shilling on a supply of tobacco that will last him for a month. The clerk with £100 a-year will walk to business in a much heavier rain than the clerk with £300 a-year; for the cost of a ride by tram or omnibus measures a greater benefit to the poorer man than to the richer. If the poorer man spends the money, he will suffer more from the want of it afterwards than the richer would. The benefit that is measured in the poorer man’s mind by the cost is greater than that measured by it in the richer man’s mind.

In other words, losing a dollar when you already have many causes less pain than when you have only a few. Marshall’s argument is the basis for both the substance and the method of a good deal of basic micro-economics: it explains the “law of demand”—why lower prices induce people to buy more—but also why tax rates should rise with income.

Economists judge the functioning of the tax system in a number of ways: certainly the system should not be administratively cumbersome, and it should, to the greatest degree possible, not cause individuals in a well-functioning market to change their behaviour. It should also treat equals equally. Finally, the tax system should raise more revenue where it will cause the least pain. And this last concern, when coupled with Marshall’s reasoning, suggests that tax rates should be progressive: as income increases, the greater the fraction that should be paid in taxes.

And this simple lesson from an economics textbook written a hundred years ago is one reason why the rich don’t want to talk about inequality, and the 99% do.

[ You can review the structure of tax rates at the federal and provincial/territorial level in Canada on the web site of the Canada Revenue Agency. Every dollar of income earned above $135,054 is taxed at a rate of 29%, while at lower income levels the rates vary from 15 to 22 to 26%. The top rates vary across the provinces, with the exception of Alberta, which taxes income at a flat rate of 10%.

To make it into the top 1% in 2010 required an income of $215,800, well above the threshold for the top federal tax rate to kick in.

Here is a spreadsheet of information on Average incomes and taxes I have drawn from the Statistics Canada website on the income shares of tax filers, which was first discussed in a January 28th, 2013 press release. I have expressed some of the information in 2010 dollars to facilitate comparisons over time, and used a measure called “Total Income with Capital Gains”. ]

Quote from the said “…….editorial in a major Canadian newspaper………” :-

“Even in Sweden, though, people say that making lots of money is an incentive to work. With globalization of everything – business, education, labour – the higher end will move higher. We still need to do our best as a society to ensure equality of opportunity, to reduce child poverty, to create good schools for everyone. ”

And there you have it! There is nothing wrong with incentives to work in the form of lots of money. But this overlooks the fact that far too many people in Canada and the U.S. have little or no incentive at all to better themselves, because of a lack of job opportunities. WHO is considering THAT? The “top 1%” (or 0.1%, or 0.01%, or whatever) don’t seem to be considering this at all, either because they don’t believe there is an issue at all or because they choose to ignore it. They seem to me to live in a different world – as compared with the rest of us, and can’t / don’t want to / relate to OUR world.

You will also probably find that the “top1%”, etc., being comfortably employed, also believe there are “…lots of jobs…”, or some such. That idea is all very well for people who are comfortably employed – with their retinue of professional referees, access to jobs posted on corporate intranets, or the jobs they will hear about through “word of mouth”; there is actually nothing wrong with this, IN ITSELF. But a given organisation, at any given time, might have 5 to 10 times as many jobs posted on its corporate intranet as it has posted on its public web site – for obvious reasons. The jobs posted on its corporate intranet, or advertised by word of mouth, will also be visible or known to a very small number of people compared to what would happen if the same jobs were posted on its public web site. So whereas there might be only 10 people or fewer competing for a job posted on a corporate intranet, that same job would likely attract between 70 and 5,000 applications if it were posted on a public web site. See my web site at http://www.unempgeninfo.com

This is basic to determining the probability of success of any one job application – and the time required to find a job, if you are on the “outside” with no access to jobs posted on corporate intranets. People comfortably employed – “insiders” – can’t see this and aren’t interested (a) because it’s irrelevant to their own lives, and (b) they aren’t interested anyway because they have other far more interesting things to do. The “insiders” and people in the job-getting-advice “industry” also like to tell job-seekers (a) that they “…have to know somebody…” in order to get a job, and (b) like to lecture endlessly about all aspects of “appearances” – resume writing, interview technique, cut and colour of business suit, “body language”, “elevator pitches” etc. , and the so-called “hidden job market”. They also seem to me to be in the business of constantly inventing new ways to insinuate that the job seeker is always “wrong” if he/she has persistent trouble getting job. Meanwhile, nobody does anything significant about the underlying fundamentals such as supply of jobs relative to demand, access to retraining etc.. The constant and un-questioned mis-use of terms such as “…given up looking for work…” and “….dropped out of the labour force….” in Statistics Canada reports appearing in the media, and dysfunctional federal and provincial government rules restricting who can access retraining, are constantly helping to keep this mess going. Utter incompetence and utterly dysfunctional.

As far as I’m concerned, this is all about keeping people confused and harassed in order to control them and keep them pre-occupied with self. All it’s actually doing is diminishing their intelligence and range of thought concerning the problem, and suppressing rational discussion about it. This way the “top 1%” etc. can appear at all times to be “tough” within their own little workplace and social cliques, and “in control” of the other “99% plus”. It’s just like what George Orwell describes in in 1949 novel, “Nineteen Eighty Four”, concerning the activities of the Ministry of Truth, the Thought Police, Big Brother and the use of the “rocket bombs” to keep the Proles frightened and under control.

Do we want a Canada like this – where the “top 1%” etc. are allowed to employ this popular incompetence, combined with all the popular myths, in order to procure cheap labour and cheapen people, thereby preventing large numbers of people from performing their functions of (a) contributing to the economy in general, and (b) being factors of production tax revenue?

And the problems that I referred to above, concerning job markets and how they actually work in practice, are not the only problems that are constantly making trouble for job seekers.

It’s important to include the Capital Gains component as you have done, notwithstanding the noise from normal stock market cycles, changing cap gains inclusion rates for taxes, and changes to tax-exemptions (lifetime limits that ended when I first started paying taxes 😦 and TFSAs that have only been introduced recently, too late to give me and other boomers the full benefit of time/compounding).

In terms of income concepts, it’s also worthwhile to point out that data from Income Tax and Statistics Canada treat all dividend income as “unearned” passive income, which is not entirely valid. Incorporated self-employed owner-operators have the option of drawing their income as dividends or wages. The optimization equation (pre-TFSA at least) was to maximize earned income for RRSP purposes and to minimize taxes via dividend tax credits. Methods exist to estimate the passive vs. active investing components using the microdata, but the numbers have not been published since 2000 or so. I’d be happy to provide more details to anyone interested in this aspect of the issue.

Oh, and I forgot to mention thanks for the spreadsheet – it’s a real time-saver and very interesting!

The Alfred Marshall reference is interesting as well. What’s that old expression about “those who forget history…”? I like to refer people to FDR’s Letter to Congress from 1938, available here:

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=15637#axzz1Q2kOsb00

I’m not sure if we even have many of these statistics anymore, let alone many leaders who are able to use them and make the linkages that FDR did. Interestingly enough, by defending competition, FDR was fighting to save capitalism, although the “spin” would be that he was being a radical interventionist.

This “99%” nonsense has to stop. It does not exist in any meaningful sense.

Canada has become a low-tax country by OECD countries. Now it’s certainly true that we need more tax brackets etc. and there’s been a flattening of the tax rate.

But…the personal tax cuts since 1995 not just on the rich but middle income earners has to be reversed if we want a progressive, redistributionist state.

The split in terms of who benefits from those who are hurt by cuts in public spending vs. those who benefit from the tax cuts is more like 75/25 – not 99/1.