The targets to reduce income poverty in Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy take an important step toward the first UN Sustainable Development Goal addressed to ending poverty, but progress will fall short without all Canadian governments—not just the federal, but also provincial, and municipal governments—adopting coordinated policies to eliminate deep poverty.

The first UN Sustainable Development Goal is to “End poverty in all its forms everywhere,” and has explicit targets associated with it.

Two of these targets are particularly relevant for Canadians. They speak to ending income poverty, and are:

By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, measured as people living on less than $1.90 a day

By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy is informed by both of these targets, setting a nationally appropriate poverty line, and using it to explicitly adopt the second target. However, it addresses the first UN target only partially: offering an appropriate definition of extreme poverty, but not adopting an explicit target.

Eradicating extreme poverty will require all governments in the Canadian federation—not just the federal—to pursue consistent and coordinated policies. Significant progress will only happen with the partnership and commitment of the provinces and municipalities.

The Canadian Poverty Reduction Strategy takes a major step

The United Nations uses the proportion of the population with less than $1.90 a day as the indicator to monitor progress in meeting the End Extreme Poverty target. While this poverty line may or may not be a useful standard for countries with higher incomes per person, the notion of extreme poverty is still important and useful.

The United Nations calls on countries to monitor the second goal by using the “Proportion of population living below the national poverty line, by sex and age.” Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy follows this recommendation, and establishes an official poverty line for Canada that can be used to monitor progress with sufficient demographic detail.

The Strategy sets a pair of Canadian targets that are directly informed by the second of the two UN income poverty targets:

By 2020, reduce the rate of income poverty by 20 percent

By 2030, reduce the rate of income poverty by 50 percent

The first Canadian target is an immediate goal, corresponding roughly to the five-year horizon of a federal government mandate. It is meant as a way of holding the current government to account. The second target is exactly inline with the UN 2030 goal.

The baseline for these targets is the poverty rate during 2015, when Canada adopted the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the year in which the current federal government was elected.

A 20 percent reduction in the Official Rate of Income Poverty from its baseline rate of 12.1 percent during 2015 implies a target of 9.7 percent, or essentially 10 percent given the inherent statistical noise. A 50 percent reduction implies a target of 6 percent.

If subsequent governments adopted the same immediate goal and were to lower the poverty rate prevailing at the beginning of their mandates by 20 percent, then the UN 2030 goal of reducing the poverty rate by half will pretty well be reached within three political mandates.

Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy is, in this sense, a major step forward in Canadian public policy addressed to income poverty.

Past governments may seem to have been more ambitious. After all, the House of Commons passed a resolution in November 1989 that received unanimous support from all parties, and committed the federal government to “seek to eliminate child poverty by the year 2000.”

But this can at best be described as an “aspirational” target. In 2005 UNICEF reviewed Canada’s progress saying the promise “has not been kept, nor has any official definition or measure of child poverty been adopted.”

Instead, Canadians fell into a trap of picking, choosing, and debating statistics, rather than monitoring progress in people’s lives. UNICEF summarized the experience by saying “Amid these definitional uncertainties, Canada’s target year 2000 came and went without agreement on what the target means, or how progress towards it is to be measured, or what policies might be necessary to achieve it.”

What is different now?

The federal government seems to have learned from this experience. Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy recaptures a bold vision, but recognizes that vision is not enough and also offers a roadmap with clear signposts to monitor progress.

The Strategy also defines and uses extreme poverty as an important signpost

Canada’s strategy recognizes the importance of giving priority to the poorest of the poor, and offers a nationally appropriate definition of “extreme poverty” that it calls “deep poverty.” The Deep Income Poverty line is associated with the cost of a minimally acceptable basket of goods appropriate for Canadians, amounting roughly to 75 percent of the official income poverty line.

It is very important to give priority to Deep Income Poverty for at least two reasons.

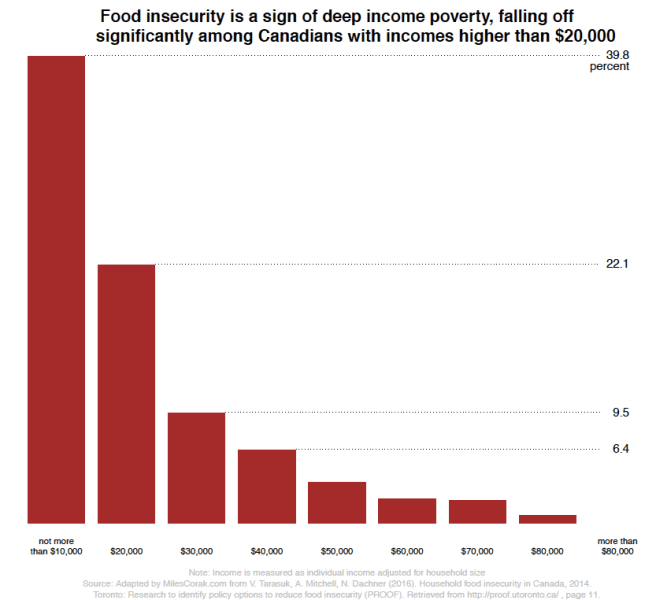

First, Deep Income Poverty is directly associated with the basic needs that the UN Sustainable Development Goals have in mind when they speak to extreme poverty. Canadians in Deep Income Poverty face much higher risks of having to make difficult choices between food, health care, housing, and other necessities, … between paying the rent or feeding the kids.

Valerie Tarasuk, who regularly reports on food insecurity with her colleagues at the University of Toronto, has said that “… food insecurity in Canada is unrelated to individuals’ skills in grocery shopping, food preparation, or cooking. Food insecurity is not a food problem, but rather an indication of profound material deprivation.”

The second reason to give priority to Deep Poverty is that it is an important complement to the income poverty target, keeping a check on perverse policy actions.

After all, the government could meet its target by taking money away from Canadians living in deep income poverty, driving them into even deeper poverty, and transferring it to those living just below the official poverty line. Moving all those living just a bit below the poverty line a bit above might be the quickest way to lower the rate of income poverty and hit the target. So, if we observe that a fall in the Rate of Income Poverty is accompanied by no improvement, or even a rise, in the rate of Deep Income Poverty, we might question the underlying moral purpose of having achieved the target.

But the Strategy does not set explicit targets for extreme poverty

The Canadian Poverty Reduction Strategy sets no explicit targets to eliminate what the UN calls “extreme poverty.” In this way it does not line up with the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Rate of Deep Income Poverty stood at 6.3 percent in 2015. If Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy had applied the 20 percent–50 percent rule to reducing it in two stages, it would have set targets of 5 percent for 2020, and 3 percent in 2030. A Deep Income Poverty Rate of 3 percent essentially means eliminating this type of poverty, given statistical noise in the data, and some continual but transitory inflow to and outflow from low income.

The Strategy recognizes that extreme poverty is not just about a lack of money, proposing to directly track food insecurity, unmet health needs, and inadequate and inappropriate housing in addition to very low incomes. All these dimensions are important to Canadians living in more challenging circumstances, but they also underscore that progress will require more than just federal government involvement: health care, housing, and basic income support falling in the jurisdictions of provincial and municipal governments.

These extreme poverty signposts need to be used to monitor the priorities, policies, and progress of all three levels of government. But there is no target to keep their priorities aligned. At the same time there is an unfortunate risk that any progress the federal government makes in dealing with aspects of the problem for which it has the tools—mostly income transfers and taxes—will lead provincial premiers and city mayors to take their foot off the gas pedal, implicitly accepting credit for seeing one poverty target achieved without paying attention to those living in the most extreme circumstances, who should in a sense be the top priority of all governments working together.

[ I was the Economist in Residence at Employment and Social Development Canada during the 2017 calendar year, working in the Deputy Minister’s office as a member of the team of public servants helping to develop Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy. During 2018 I continued to serve as a part-time advisor in the Deputy Minister’s office on this and other files. Though this post draws closely from my reading of Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy, the views expressed are entirely my own, and in particular should not be interpreted as reflecting the positions of Employment and Social Development Canada, nor of the Minister and his staff. ]

Canadians in Deep Income Poverty face much higher risks of having to make difficult choices between food, health care, housing, and other necessities, … between paying the rent or feeding the kids. And without any sort of equity or racial justice analysis the disproportionate experience of poverty of First Peoples, peoples of colour, persons with (dis)abilities, single mothers, newcomers and others – so critical to effective and needed change-making – problematically gets lost in what the author refers to as “statistical noise in the data” !?

My use of the term statistical noise is meant to refer to the inherent fuzziness in the numbers associated with the fact that the statistics are produced from a sample of the entire population, what Statistics Canada would call the “standard error”.